We helped heal the planet before. We can do it again.

In 2025 alone, wildfires caused $65 billion in damages in California, more than 2,300 people died in one of Europe’s deadliest heat waves and prolonged droughts in Somalia have left hundreds of thousands on the brink of starvation.

Climate change, driven by planet-warming pollution in the atmosphere, is changing weather patterns and making extreme weather events like these more likely. The need for decisive and collective global action to protect people from the harms of climate change has never been more urgent. At the same, progress may feel out of reach right now.

So it might surprise you to know that, almost 40 years ago, world leaders, scientists and advocates did take decisive and collective environmental action — and it has worked. That achievement is known as the Montreal Protocol.

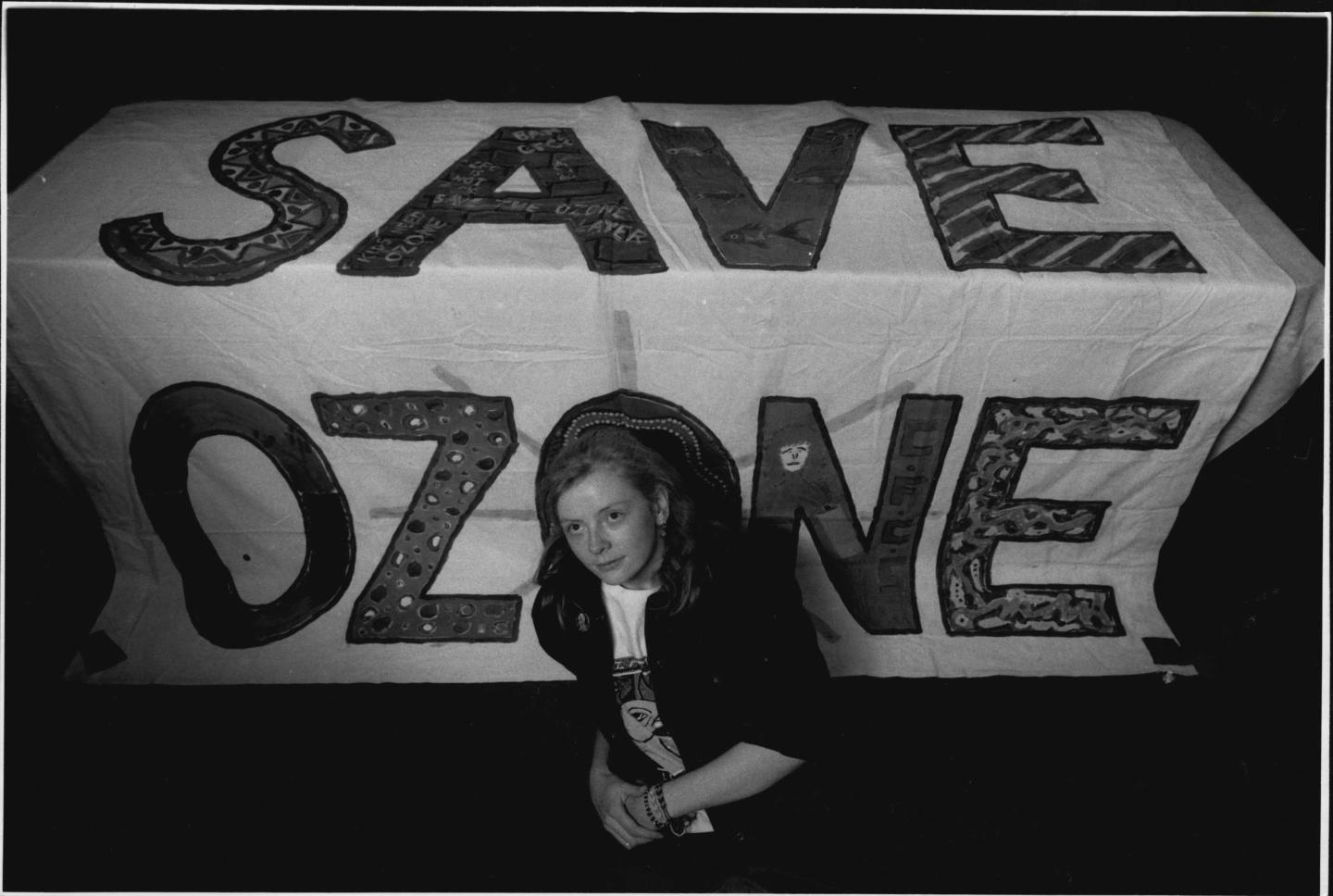

“Four decades ago, despite political backtracking and industry resistance, people stood up with the persistence, investments and activism the moment required,” explains Meredith Ryder-Rude, who directs global engagement and partnerships for the nonprofit Environmental Defense Fund.

“It’s incredible to think of all that's been saved by the Montreal Protocol, and in political times not so different from this,” says Ryder-Rude. “Not only was it the first ever global treaty to cut pollution, but it was also universally adopted by every country. And as representatives gather at the annual United Nations climate conference (COP30) this November, they must channel the same resolve to deliver on the Paris Agreement.”

What is the Montreal Protocol?

The Montreal Protocol on Substances that Deplete the Ozone Layer is an international treaty adopted in 1987. Better known as the Montreal Protocol, it is a global commitment to phase out pollutants that burned a hole in the Earth’s upper atmosphere, which protects everything on the planet from ultraviolet radiation.

The treaty targets gases that harm the ozone layer, including chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs). These versatile manmade chemicals were developed in the early 20th century and quickly became widely used: in air conditioning, refrigerators, even common hairsprays and deodorants.

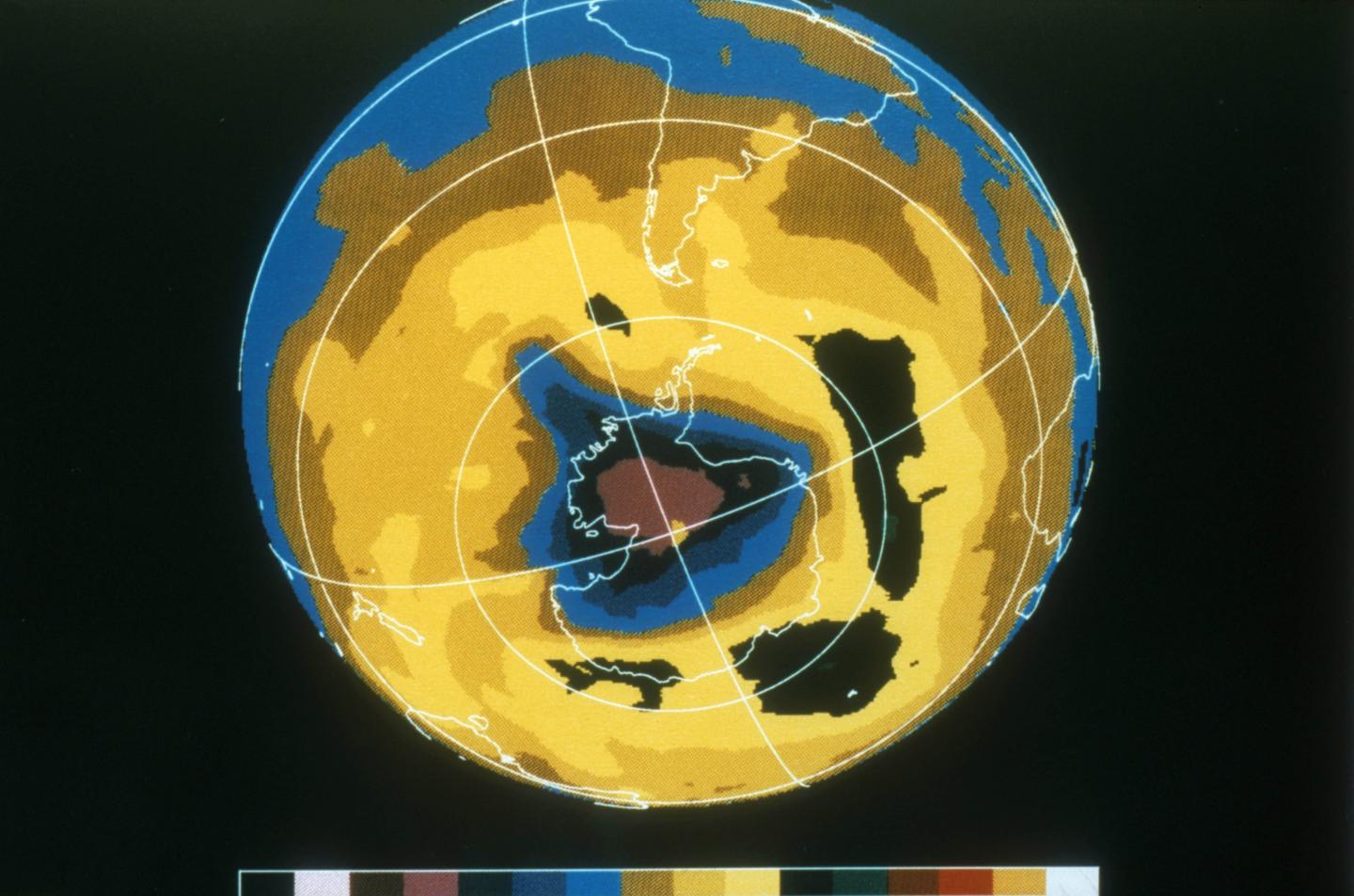

As the popularity of these chemicals increased, so did their presence in the atmosphere. The chemicals formed reactions that were depleting the ozone layer, and scientists predicted that the damage could greatly increase Earth’s exposure to harmful UV radiation. By 2047, scientists later discovered, UV radiation would have been strong enough to cause sunburn in five minutes, make skin cancer in humans and animals skyrocket and scorch the world’s food crops.

The Montreal Protocol saved the planet from that future. The United Nations treaty is credited with preventing millions of cancer deaths, hundreds of millions of cases of skin cancer, and tens of millions of cases of cataracts in the United States alone. By phasing out ozone depleting substances, which are also powerful greenhouse gases, the agreement slowed down global warming and saved countless lives. The hole that formed in the ozone layer — which peaked at 11 million square miles in 2000 — is expected to recover by 2070.

Environmental news that matters, straight to your inbox

Lessons learned from the Montreal Protocol

The Montreal Protocol was the hard-fought victory of scientists, political leaders and a concerned public. They overcame challenges that are not so different from those the world faces today. Here’s how:

1. People didn’t give up

In the 1970s, as scientists began to understand the terrifying rate of damage to the ozone layer, they left their labs and took to the media to call for action.

At the same time, a million tons of CFCs were being produced every year, representing a billion-dollar industry. Seeing these “activist scientists” as a threat to their profits, chemical companies campaigned to undermine their research. (Sound familiar?)

But major cultural shifts were happening then, too. The first Earth Day and Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring brought environmentalism to the masses. People were seeing the connection between their personal choices and pollution. And when news of the ozone layer spread, the public acted. In the U.S., states enacted bans on CFCs, Congress proposed regulations and sales of aerosol cans (a major source of pollution) took a dip.

The head of the 1987 U.S. delegation in Montreal credited its success to the role of science and the power of public opinion.

Soon, the industry would not only acknowledge the science but support a complete phaseout of CFCs. And the scientists who risked their reputations? They won the Nobel Prize in 1995.

2. World leaders came together around a shared future

The Montreal Protocol is the first universally adopted environmental treaty. But it did not happen overnight. It was not even the first time nations met on ozone depletion.

The ongoing success of the Montreal Protocol — and the future of the planet — relies on collective action. When the treaty was first passed, only 46 countries signed. Many others expressed skepticism or were concerned they could not afford CFC alternatives. But as industrialized nations acknowledged their outsized roles in the destruction of the atmosphere, they pledged vital funds to support developing countries.

“These funds were essential to empowering all nations to sign on and take action — just as climate financing reforms are essential today,” explains Ryder-Rude.

3. Advocates kept sight of the long game

At many points, it seemed like progress was locked in a tug of war. Yes, before there were climate deniers, there were “ozone deniers.”

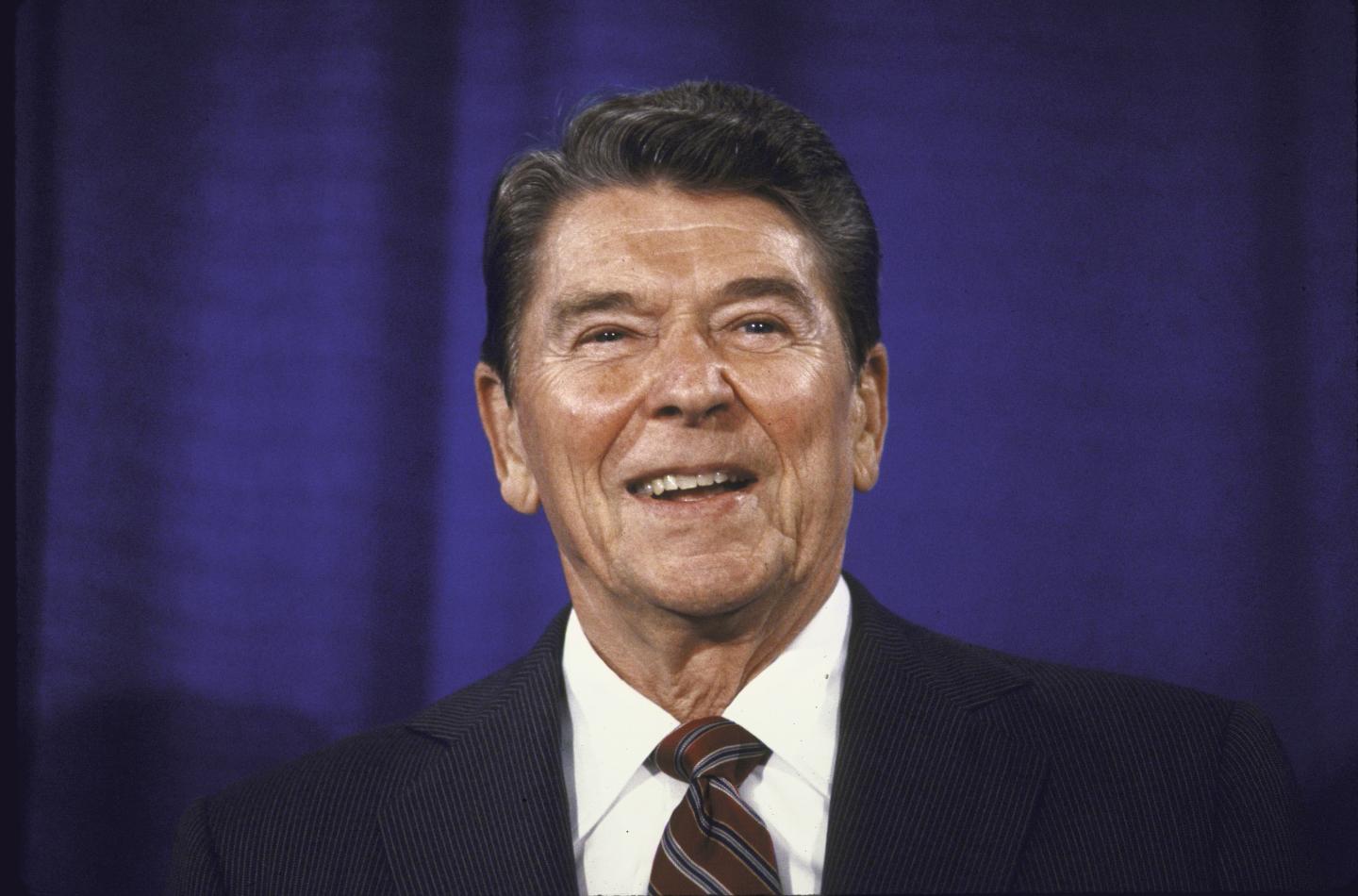

While scientists around the world continued building their case, advances in the United States faltered. After several years of progress, including a ban on some CFCs, a new U.S. administration led by President Ronald Reagan ushered in major cuts to environmental research. In response to concerns over the ozone layer, one cabinet official suggested Americans just needed to use sunscreen and hats.

The truth is, many people lost hope. But advocates kept pressing. Eventually, even major industries saw the writing on the wall. And the Reagan administration would eventually go on to lead critical negotiations in Montreal.

Today, science tells us that the initial terms set by the 1987 Montreal Protocol (50% reduction in CFCs in 11 years) would not have been enough to save the ozone layer. But nations continued to meet every year to ensure agreements reflect the latest science and to strengthen their commitments — similar to the structure of the Paris Climate Agreement, which requires parties to update their climate goals every 5 years.

Thanks to the Montreal Protocol, 99% of ozone depleting substances have now been phased out, and the world is tackling replacement chemicals that have had unintended climate impacts.

The path forward

The fight to heal the ozone layer reminds us that there is at least some precedent for these

unprecedented times. Nearly 40 years ago, the world came together to protect people from harmful pollution — a decision that, despite denials, industry opposition and political shifts, has proven successful for human health and economies worldwide.

Protecting people from the harms of climate pollution will require a similar global effort. “We need to pick up the pace and deploy the solutions we know can improve people’s health, create economic opportunities and build equality while cutting climate pollution,” says Ryder-Rude.

Those solutions include speeding up the global rollout of clean, renewable energy and cutting the methane pollution that is accelerating global warming. Managing forests to prevent wildfires and protecting the ocean’s ability to store carbon can also fight climate change and support communities. When people from nearly every country in the world gather for the COP30 global climate talks in Brazil, solutions like these point the way forward.

“The Montreal Protocol is the story of how humans stepped up to fight the biggest man-made environmental and public health threat the world had ever seen to that point,” says Ryder-Rude. “The story of climate action is still being written.”