The Trump administration is wiping out scientific data on climate change. The data heroes are ready.

In the early hours of a March morning, librarian Julia Martin got word that a government data server containing critical climate information was at risk of going offline. Since President Trump’s return to office, his administration has purged more than 8,000 government web pages and 3,000 datasets — scrubbing climate, health and environmental justice information from sites run by the Environmental Protection Agency, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and other agencies.

Martin, director of information services at the nonprofit Environmental Defense Fund, sprang into action. Fortunately, EDF had already been participating in the End of Term Web Archive project, a national initiative to preserve public government websites during presidential transitions. Through this effort, Martin knew where to find archived data and how to use existing aids to assess what had already been saved.

That advance work paid off. Rather than scramble to recover lost data, Martin discovered that much of the material had already been captured. While EDF initially planned to back up recent updates, the government ultimately renewed the server contract — making additional downloads unnecessary. But the availability of these archives ensured EDF and other organizations that depend on this data could keep working without disruption.

In a high-stakes digital tug-of-war, a scrappy network of scientists, archivists and volunteers is racing to rescue climate and environmental data — vital information that can save lives and help steer the planet toward a safer future. Groups like the Environmental Data & Governance Initiative (EDGI), the Data Rescue Project and Harvard’s Library Innovation Lab are working to preserve critical federal datasets as the Trump administration purges information that runs counter to its agenda of promoting fossil fuels and undoing pollution safeguards.

Behind the scenes, a decentralized army of volunteers is preserving key federal information piece by piece. From university libraries to kitchen tables, they’re using tools like the Internet Archive’s Wayback Machine and Harvard’s Perma.cc to capture disappearing content. Harvard’s Environmental and Energy Law Program helps archive complex datasets through its Dataverse repository, while the End of Term Archive sweeps up entire websites during presidential transitions.

A bonfire of scientific knowledge

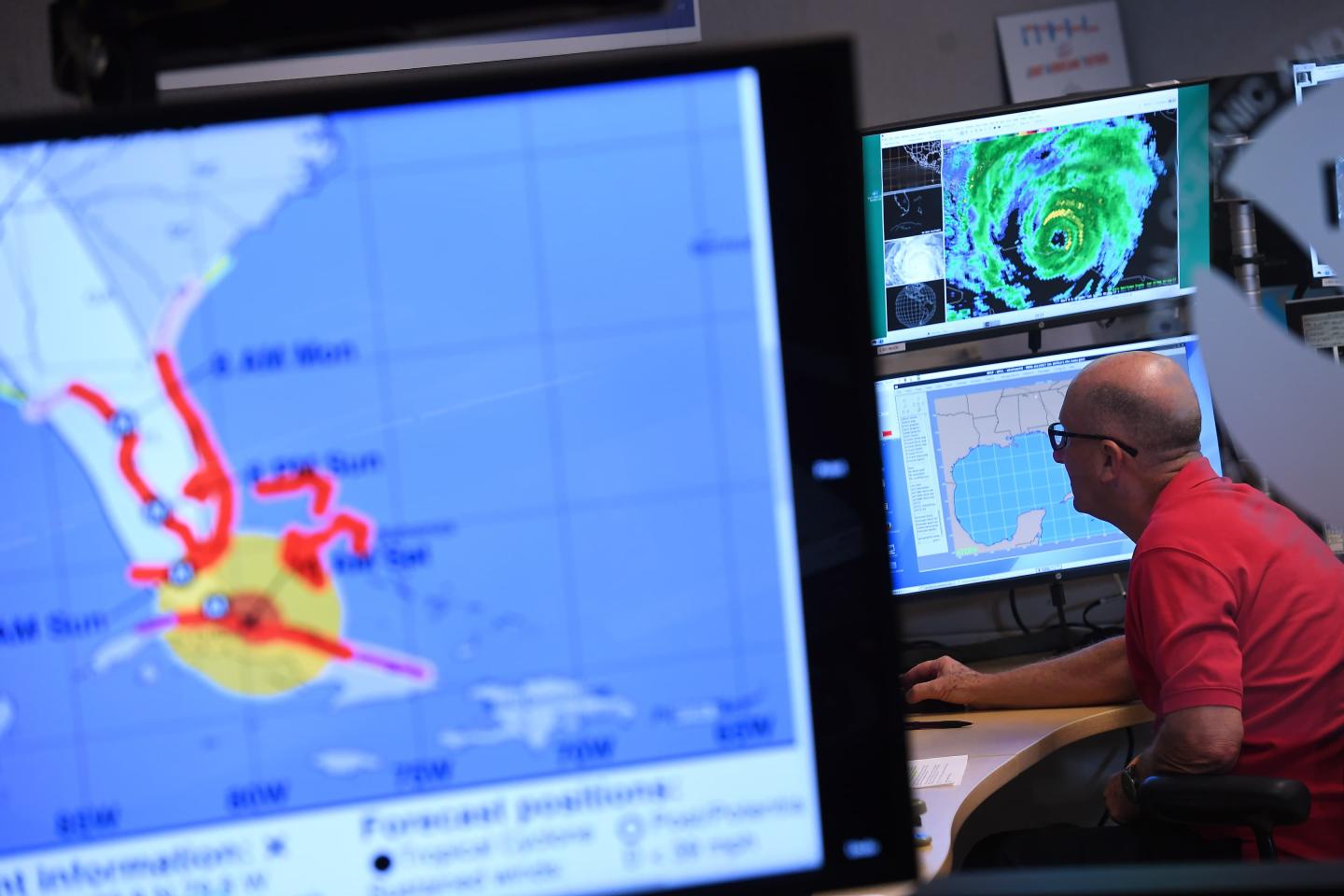

These aren’t just files — they’re the foundation for protecting people and the planet. Climate scientists rely on NASA satellite data and NOAA weather records to track and understand changes in the Earth’s air, water, forests and other natural systems. Their analyses can then be used to guide efforts to protect these systems, which support our health and economies. Decision makers use these same sources — alongside U.S. Census data — to identify which communities are most vulnerable to climate change.

Every day, people visit the websites of EPA and other government agencies to learn how to protect their health and homes and to monitor what the government is — or isn’t — doing in response to environmental threats. When key data or digital tools suddenly disappear, the work of scientists, community groups and even government agencies can stall. The federal government not only collects environmental data — it generates the science that public health and protection programs depend on, especially at the state level.

“If we lose environmental data, we limit our capacity to respond to climate threats,” says Ellen Robo, a transportation and clean air policy expert at EDF. “You can’t protect what you can’t measure.”

For farmers, the data purge has brought immediate, tangible impacts. When the Department of Agriculture removed climate risk models and crop-resilience tools, it stripped away planning resources farmers rely on to manage droughts, floods and shifting growing seasons.

“Taking away information that allows farmers to make decisions about their business, and that also protects the planet, protects their soil, enhances their crop yields, it’s really insane to be doing that,” said organic farmer Wes Gillingham, in an interview with Grist.

Julia Martin Director, Information Systems at Environmental Defense FundWe’re focused on not just scrambling to save the next dataset, but creating resilient, redundant systems that don’t rely on the goodwill of whoever’s in power.

Organizing the defense

Gretchen Gehrke, EDGI co-founder, was among those who sprang into action in 2016 as public datasets vanished under the first Trump administration. “Back then, we thought we’d learned enough to stop this from happening again,” she says. “But this time, they’re playing by a completely different set of rules. It’s a slash-and-burn approach — moving fast and doing as much damage as they can before the courts can stop them.”

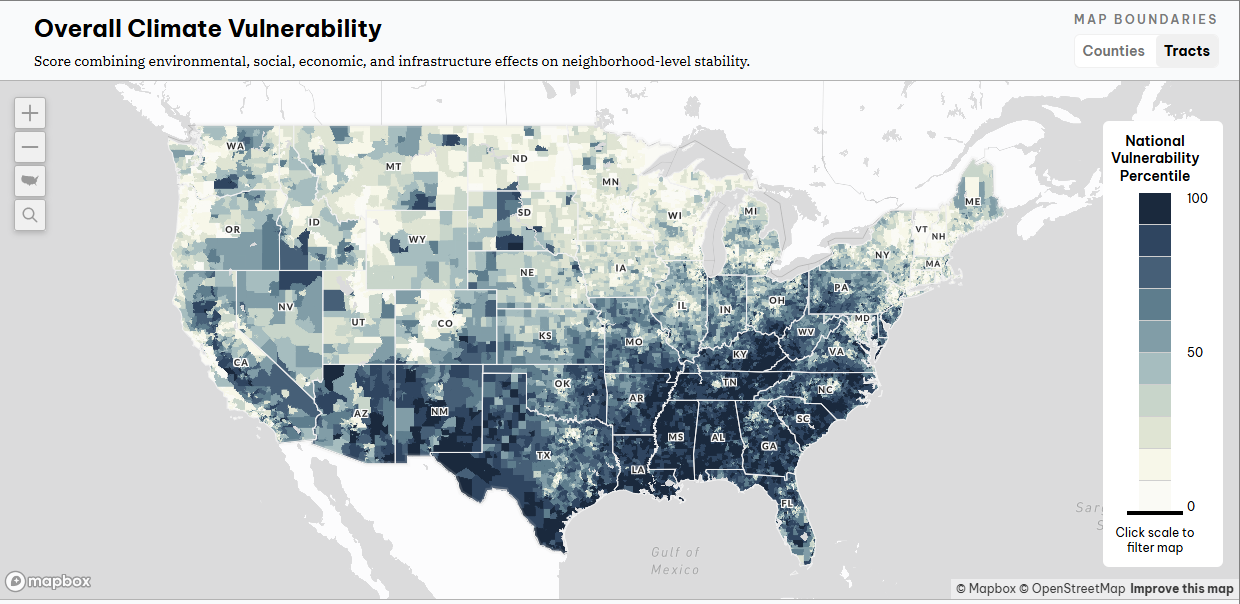

In anticipation, EDGI canvassed environmental NGOs and local governments in late 2023 to identify high-priority datasets. The most urgent: the Climate and Economic Justice Screening Tool and EJScreen, which highlight communities facing disproportionate climate risks and burdens of pollution. When those tools disappeared from federal websites, EDGI rebuilt them within three days.

EDF also sprang into action. “Those of us who were around during the first Trump administration remembered how climate information vanished almost overnight,” says Jennifer Freeman, part of EDF’s legal team. “So, when this new wave started, we immediately reached out to EDGI to help triage what needed to be saved.”

That included the Inflation Reduction Act Tracker, an EDF tool that depends on government data to catalog every climate-related provision of the massive Biden-era legislation, which included $369 billion in funding to tackle climate change — funding that the Trump administration and some members of Congress are currently trying to claw back.

“We spent weeks compiling spreadsheets of every link on every page,” Freeman recalls. “It was tedious. It was necessary.”

After the Trump EPA failed to release its legally required greenhouse gas inventory, a yearly account of U.S. climate pollution, EDF stepped in — using a Freedom of Information Act request to recover and publish the missing data. Bringing the report back into public view helped fill a major information gap and revive a critical tool for holding polluters accountable and informing climate action.

But not all content is easy to save. Interactive tools like EDF’s Air Tracker and Climate Vulnerability Index — both of which rely on government data — require manual intervention.

Air Tracker uses real-time wind and emissions data from agencies like the EPA and NOAA to trace pollution back to its source. The Climate Vulnerability Index combines environmental hazards with census, socio-economic, health and other data to show which communities face the greatest threats.

These aren’t just websites — they’re dynamic tools built on live data feeds. When the data disappears, so does their power. Archiving them means preserving both functionality and data flow.

“There are things a crawler just can’t handle,” Robo says. “Interactive maps, layered datasets, anything graphics-heavy — those had to be preserved manually.”

Environmental news that matters, straight to your inbox

A blueprint for the future

From the collapse has come resolve. EDF, EDGI and their partners aren’t just rescuing data — they’re building a more durable system: a justice-centered environmental data infrastructure.

“We’re focused on the long game now,” Martin says. “Not just scrambling to save the next dataset, but creating resilient, redundant systems that don’t rely on the goodwill of whoever’s in power.”

Public trust in science depends on transparency and access. Archiving isn’t enough. The goal is permanent, public access to the information people need to prepare for climate disruption and hold governments accountable.

Despite the urgency, there is hope — rooted not in faith but in focused, coordinated action. EDGI has already preserved more than 130 major datasets, with another hundred underway. The Climate Program Portal, maintained by Atlas Public Policy, remains online and regularly is backed up.

“We care deeply about facts,” Gehrke says. “For our society to heal, we have to return to a shared foundation of truth. We can disagree on solutions — but we need to begin with the same reality.”

That foundation is being rebuilt now — dataset by dataset, server by server, hero by hero.

“This isn’t just a salvage operation,” says Freeman. “It’s resistance. It’s restoration. And it’s preparation.”