“Has everyone been fed?’’ North Carolina, one year after Hurricane Helene

Shrinking support from the Trump administration delays disaster recovery, leaves communities vulnerable to dangerous weather.

The Black Mountain Presbyterian Church campus in western North Carolina, pressed into the Blue Ridge Mountains like a thumbprint, surrounded by impossibly thick forest and punctuated with Black-eyed Susans and other native plants, is a few miles from Mount Mitchell, the highest point east of the Mississippi River.

“Closer to God,” Mary Katherine Robinson, the church’s pastor and head of staff, joked.

A year ago, Robinson had been preaching for a few Sundays in a row about the church’s new mission, which had taken the form of a question: Has everyone been fed?

Then Hurricane Helene hit and gave it a resonance that has changed Robinson forever.

Hurricane Helene devastated North Carolina mountain towns like Asheville (River Arts District, left) and Swannanoa (right). (Stephan Pruitt/Fiasco Media)

Disasters had happened in North Carolina before — many people are still on a first-name basis with the worst of them, Floyd, Hugo, Matthew, Fred — but none like Helene. It was the deadliest hurricane in the U.S. since Katrina in 2005, causing at least $60 billion in damage in North Carolina alone. After making landfall in Florida and blowing into the region on Friday, September 27, 2024. Helene turned the mountains into rivers. Its rainfall, intensified in a world being overheated by climate-altering pollution, smeared the landscape with roiling landslides, as life-giving waterways turned life-threatening and debris crashed downward, taking out tree after road after bridge after home.

No one had power. No one had water. No one had cell service or internet access. No one could get cash from an ATM or swipe an EBT card or call anyone else for help. Ruthlessly, Helene revealed that the region had deeper needs for essential access to food, housing and transportation than most everyone knew. And it has revealed in the long year since that most people’s ability to get back to where they started, let alone to a safer, stronger foundation, requires more than even the most heroic, most generous community can provide — and much more than what they have been getting from the Trump administration to date.

President Trump visited Asheville just four days after he was inaugurated for his second term, saying, “I’ll be taking strong action to get North Carolina the support that you need to quickly recover and rebuild.”

Since President Trump left Asheville, he’s called for the elimination of the Federal Emergency Management Agency and told states to expect “less money” for disaster recovery. His administration has sought to divert hundreds of millions of dollars from FEMA’s budget, fired and forced out almost a third of its permanent staff, selected an acting administrator who reportedly did not know the U.S. has a hurricane season and canceled billions of dollars more in grants that were helping other communities across the country prepare for the worst, strengthening utility poles, protecting drinking water systems, and rebuilding roads and bridges.

This summer, the administration also started taking steps to revoke the federal government’s longstanding scientific determination that climate change presents a threat to people’s health and safety.

North Carolina wasn’t responsible for Hurricane Helene, but it’s been left on its own to try to heal.

Communities caring for each other

That first weekend, Black Mountain Presbyterian’s parking lot became a disaster hub. It was the one spot in town where anyone could get a cell signal — only one bar, but still. Church staff rolled out gas tanks and grills and started cooking the inventory of frozen hot dogs and hamburgers that had started to thaw.

Pastor Mary Katherine Robinson of Black Mountain Presbyterian Church (left); the church became a volunteer-run distribution center. (courtesy Mary Katherine Robinson)

By the end of the first week, they were feeding close to a thousand people. The same parking lot now hides mounds of Helene’s debris — branches and brush too big to compost. It’ll still break down, but it’ll take years. The disaster created more than 11 million cubic yards of debris, enough to fill about 1 million dump trucks. In Canton, 30 miles west of Black Mountain, the debris are being burned in so-called “stump dumps.” One mulch fire at a landfill has been smoldering out of control all summer long.

“Nobody in southern Appalachia can breathe right now,” Kasey Valentine-Steffen said.

Valentine-Steffen, whose family has called these mountains home for at least seven generations, was stuck on her porch as the floodwaters rose. Once they started to recede, it didn’t take long for her to hear chainsaws firing up. Young people got into their trucks to drive to hard-to-reach places to start mucking out flooded houses.

“We’re big on community care,” she said. “In southern Appalachia, you could walk up to people, and their house would be floating away behind them, and you’d say, ‘Here, would you like this bowl of food?’ And they’d be like, ‘No, give it to my neighbor, they need it more.’”

She’s been at the heart of this homegrown social infrastructure for years. As head of the North Carolina Community Health Worker Association and a lactation consultant at the region’s largest pediatrician’s office, Valentine-Steffen cares for a living, but it’s also how she lives. Her father was a union organizer at the local paper mill. During the pandemic, she put 2,500 miles on her vehicle just checking on people, making sure they had what they needed.

“I’ve had four days off since Helene,” she said.

The Appalachians, she stressed, have always been a place for people who are seeking refuge, who know how to take care of themselves, who might not want to be found. The geographic isolation can make getting help in even harder.

Haywood County, where Valentine-Steffen lives, according to Environmental Defense Fund’s U.S. Climate Vulnerability Index, doesn’t have many roads to begin with, and they’re at an extremely high risk of flooding. The county ranks in the 99th percentile nationally for transportation vulnerability. And it has less access to health care than every other county in North Carolina.

“People are living right on the edge,” she said. “We’re weary, but we just have to keep taking care of the person next to us.”

Environmental news that matters, straight to your inbox

Exhaustion in Asheville

Gray Jernigan knows just what she means. Growing up in Raleigh, he was used to hurricanes. But this was his first disaster as a parent. “It’s exhausting what we’ve been through,” he said.

Jernigan lives with his now-3-year-old son and wife across the French Broad River from Asheville’s River Arts District. The Friday Helene hit, he was planning to join a conference call for work, but communications went out. His family walked from their house down to the Haywood Road bridge, where hundreds were standing and watching ”buildings wash away.”

No one had access to the news, so no one was sure what was happening. Jernigan knew it was serious when he started hearing the heavy clank of propane tanks, shipping containers and semi-trailers slamming into the bridge beneath them.

Once there was an interstate cleared of landslides, the family evacuated temporarily to Raleigh, so their son would have access to clean water. As deputy director of a local environmental nonprofit, MountainTrue, Jernigan drove back alone to join the recovery effort in what had become “an empty city,” spending all day distributing food, testing water quality and talking with people about their needs, before returning to an empty house and pulling water from a creek just to flush the toilet.

Debris kept piling up. As the recovery shifted in the months to come, Jernigan’s organization worked with state elected officials to allocate $20 million just for debris removal. The state environmental agency used $10 million of that to hire 100 workers, many of whom had lost their jobs in the region’s outdoor tourism industry, which the disaster decimated, too, for the next 18 months.

Economically, physically, mentally — the recovery is going to take much longer than that. ”I think we’re just beginning to understand the psychological impact,” Jernigan said. “You’re driving your kid to daycare, seeing your community covered in trash, and you pass through the disaster area, and then you go to work. What does that do to you? I’ve been seeing it in my son. We talk about it. Hey, why‘s that building damaged? Do you remember the big storm? It’s something that’s going to stick with him, stick with all of us.”

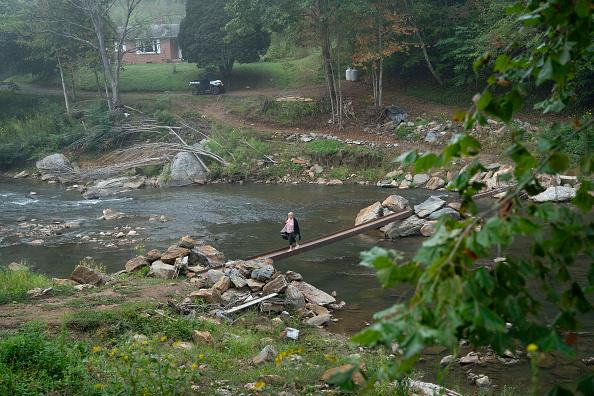

North Carolina has only received 6% of the federal disaster aid it requested, making recovery frustratingly slow. In Burnsville, residents crowd-funded a metal footbridge to replace the one that was washed away by Helene. (Allyn West; Getty)

Forty percent of North Carolina’s population lives in a federally declared disaster area. The state requested federal funding to cover 48% of Helene’s economic damages, but a year later, less than 10% of that money has been received.

Asheville Mayor Esther Manheimer and Gov. Josh Stein met with the state’s representatives in Congress to make clear the outstanding need. Aid appears to have taken a back seat to President Trump’s avalanche of executive orders and newly implemented Department of Government Efficiency processes. Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem required her personal sign off on any cost higher than $100,000, creating months of frustrating delays.

The FEMA Act that recently passed on a 57-to-3 bipartisan vote out of the House Transportation and Infrastructure Committee underscores that the recovery after Helene has been hampered, and states need more from the federal government.

“I don’t think anyone can say that disaster recovery has ever been perfect,” said Will McDow, who lives in North Carolina and works on climate change resilience for the nonprofit Environmental Defense Fund. “But over the years, FEMA has undergone critical reforms to improve disaster response and invest in proactive strategies that save lives and reduce long-term costs. Dismantling these improvements without a clear, evidence-based plan will leave communities more vulnerable when disaster strikes.”

Has everyone been fed? Before Helene, Robinson said, parishioners were encouraged to take it literally, to answer the question, even to yell, if they wanted, and the answer was always a yes or a no. Ever since, though, they’ve changed it. Now, she asks, “Has everyone been fed?”

And now they all say, Not yet. Not yet.