In extreme weather, electric vehicles keep the lights on at home

Equine veterinarian Dr. Erica Lacher doesn’t consider herself much of a car person. But she started falling in love with her car — an electric Kia EV 9 — last year, thanks to the huge amount of money she was saving on gas and maintenance; the fact that as a vet, she could drive out to a farm and work out of the back of her car without inhaling exhaust; and the way it performed on the road.

“I didn’t used to be a brave, go out, go fast and fly-around-the-corners kind of driver,” she says. But with her electric vehicle, “it’s fun racing teenage boys and hurting their feelings.”

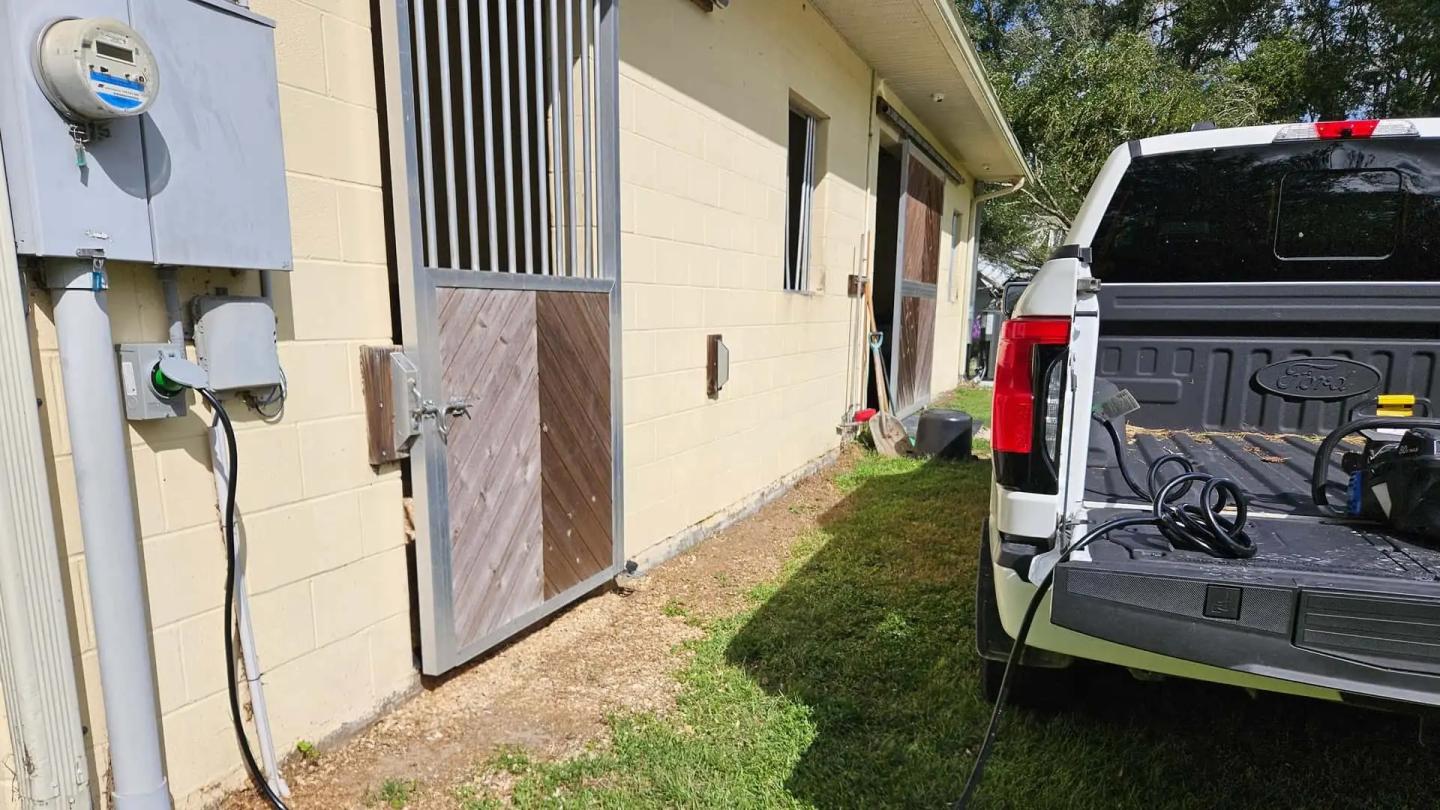

Still, what really sealed the deal was the way the SUV powered her veterinary clinic in north central Florida through and after Hurricanes Debby and Helene, running its computers, phones, equipment and refrigerators filled with $15,000 worth of perishable medication. In Helene’s aftermath, along with her husband’s electric Ford F-150 Lightning, the SUV powered an annual community festival for 200 people, complete with performers and a booming sound system.

“Many people didn't have power at home that day, so it was something to do besides storm cleanup for those that could get out,” says Justin Long, Lacher’s husband, who is the practice’s administrator.

This summer will likely be another of the hottest summers on record. And as hurricanes and wildfires barrel in, turbocharged by the fossil fuel pollution that's warming the planet, one group of people is feeling more secure, not less, about their ability to power through electric service disruptions: A growing cadre of electric car and truck owners who are benefitting from their vehicles’ abilities to power their homes and offices.

A car that can power your house

“Electric cars and trucks are essentially big batteries on wheels,” says vehicle electrification expert Neda Deylami of the nonprofit Environmental Defense Fund. “A lot of people know about the benefits EVs offer society as a whole, including a lot less climate and air pollution than gas-powered cars. But fewer people know that they can really save you when the grid goes down.”

While most early-generation EVs officially only accept electricity, more and more new EVs allow two-way, or bidirectional charging — they can draw power and also give it back.

There are many ways to connect an electric vehicle to a home, running the gamut from DIY kits to $5,000+ packages that sense when the grid goes down and kick in automatically. (Car owners have to pick up the tab for these themselves; none of the options come standard.)

Chris Dolberg, an IT manager in Ben Lomond, California, has a Ford F-150 Lighting with a host of outlets built in: 10 120-volt outlets that work just like any building wall outlet, allowing him to plug in a cellphone, coffee pot or circular saw — and one 240-volt outlet that can supply power to his whole house. “We’re up here in the mountains. We lose power all the time,” says Dolberg. “After the first winter, when we lost power a bunch of times, my wife was like, ‘This is the best thing ever.’”

Dolberg connects his truck using a kit that interfaces with his home’s breaker box, a solution he installed himself using parts costing $150. (Installations like these should be done by qualified technicians.)

Liz and Glenn Peterson of Asheville, North Carolina chose the $200 adapter route. After Liz bought her Hyundai Ionic 5 in February 2024, Glenn, a true romantic, got her the adapter for her birthday the next month. “I laughed because I thought, ‘Oh, we’re never going to need to do that, right?’” she says.

But six months later, the couple lost power for a week after Hurricane Helene devastated western North Carolina. Plugging the car into an extension cord and power strip, they were able to run their fridge, coffee maker and lights, with plenty of battery left over once their electricity was restored. In fact, the Ionic’s battery pack, charged to 80% before the storm, was at 71% when the power returned.

“Had I known it would work this well,” Glenn says, “we would have plugged in more things.”

Environmental news that matters, straight to your inbox

Affordable, reliable backup power

While news about using EVs as backup power has yet to spread widely, “I think that there’s a real future here for individuals dealing with disasters, which will become increasingly common because of climate change,” says Liz Najman, director of market insights at the EV analytics firm Recurrent.

Energy security was definitely something Michael Cowan had in mind when he put down a deposit on his F-150 Lightning. (That and the rocket-like acceleration.) He cares for his elderly grandmother in his home in Washington, D.C., where power disruptions regularly mark the dangerously hot summers.

“It’s not easy to take care of the elderly without power at the ready,” says Cowan. “But we have continuous power the entire time. It’s about her comfort and making sure she has what she needs.”

His home has since become a haven for his neighbors, too, when the power goes down. “Most of the time, they just want to come in and get cool with the AC,” he says. “But they’re still amazed by the features like powering the house that I’ve grown so used to.”

Like any car, truck or backup generator, EVs are vulnerable to floods and storm surges. In rare cases, saltwater seeping into EV batteries can cause fires, says Najman. “That’s why it’s important to move any car to higher ground during a storm.” (Despite the viral videos of electric vehicle fires, gas-powered cars are more than 60 times more likely to catch fire than EVs, according an analysis of data from the National Transportation Safety Board.)

EVs can also offer benefits that fossil-fuel-powered backup generators can’t match. They’re quiet and don’t pollute the air or warm the climate. They can provide power for as long as a week on a single charge and can often operate when backup generators can’t — because in many cases, the same disasters that bring down the grid can also hamper fuel supplies.

One of the Petersons’ neighbors, for instance, had a portable backup generator that turned out to be useless during Helene. Without electricity, local gas stations couldn’t pump the gas those neighbors needed to fuel their generator. And with blocked roads preventing deliveries, many stations had no gas to pump even after power was restored.

EVs also often compare well on price. A whole-home generator can cost between $8,000 and $25,000 to install and running one can cost upwards of $90 a day. By contrast, the purchase price for EVs with two-way charging is often — though not always — comparable to similar gas-powered cars. And filling up with electrons is generally far cheaper than filling a gas tank. Depending on location, juicing up a Kia EV9 can cost between $13 and $48. A full tank for a similarly-sized vehicle would cost about $62 and won’t power your home.

Those calculations reframed the way Dolberg thinks about the cost of his truck, which was more expensive than some gas-powered F-150 models. “I knew I was paying a premium,” he says. “But I didn’t want to spend $10,000 on a generator that is used infrequently, requires maintenance and that might not always be there for me.”

The experience of many EV owners can put to rest the idea that a gas-powered car is more reliable in an emergency.

After Hurricane Helene, gas lines in Asheville were so long they reminded Liz Peterson of the 1970s oil crisis. She and her husband were able to sail past those lines in their electric car, which still had plenty of charge left after the power came back.

“We’re so used to gas vehicles that we think they’re more reliable and gas is more accessible,” Glenn says. “That was not the experience during Helene. It just wasn’t. I’m grateful we had the EV.”