Hungry for brains, false climate information spreads worldwide

As wildfires raced across Los Angeles this winter, something almost as dangerous was rapidly spreading online — climate disinformation.

Baseless claims that the fires were started on purpose to make way for renewable energy projects, or a high-speed railroad line, took hold and spread across social media like a spark in dry grass. Some of the claims were even supported by realistic-looking AI-generated images, such as one appearing to show a fireman intentionally starting a fire.

According to Global Witness, climate disinformation is false or misleading information about climate change and the solutions that can help, which is shared with an agenda in mind — to deceive people, promote a political view, make money or stir up tension.

Phillip Newell, communications co-chair at Climate Action Against Disinformation, has an even more direct definition: “Wrong about climate change, on purpose, for money.”

A new age of lies

Climate disinformation isn’t new. It’s about as old as climate science itself. But it’s mutating and growing fast. Long gone are the days when climate disinformation only took the form of climate denial — people claiming that climate change isn’t real or at least not caused by human activities. As the devastating reality of climate change-fueled extreme heat, wildfires and floods has become ever more inescapable, purveyors of climate disinformation have shifted strategies. Straight-up denial still exists, but more subtle messages have begun to take over, such as claims that while climate change might be real, it’s too expensive to do anything about; or, everyone likes warmer weather; or, that more CO2 just means more food for plants; or wind turbines kill wildlife.

“Attacking climate solutions, instead of climate science, has become the norm,” says Dr. Anthony Leiserowitz, director of the Yale Program on Climate Change Communication.

Climate disinformation is also spreading to new places. Once largely confined to the United States, Canada, Australia and, to a lesser degree the U.K., as climate action has begun to spread around the world, climate disinformation has followed closely on its heels. Improvements in translation tools and the widespread adoption of communication platforms like WhatsApp and TikTok mean that disinformation that pops up in one part of the world can circle the globe in a matter of seconds.

Dr. Anthony Leiserowitz Director, Yale Program on Climate Change CommunicationClimate disinformation is like zombies. Incredibly difficult to kill and always hungry for more brains.

The exact narratives vary from country to country depending on the local social, economic and political tension points. In Brazil, where the Amazon rainforest plays a vital role in soaking up carbon, large agriculture companies who want to clear forest for cattle grazing are behind the lie that climate change is made up by liberal elites in America who want to keep Brazil from reaching its full economic potential and becoming a bigger player on the world stage.

“Climate disinformation poses a significant challenge to climate action globally,” says Ava Lee of Global Witness. “It erodes public trust in scientific institutions. It makes it harder for climate activists, scientists and even weather reporters to do their jobs. And it divides public opinion and hinders collective action.”

While it may seem like climate disinformation just organically crops up — it doesn’t. Newell describes the technique as corporate-fed industrial astroturf, as opposed to grassroots. Just like the tobacco industry intentionally sowed doubt about the harmful effects of smoking, he says, people who have made their fortunes from oil and gas, like the Wilks and the Koch brothers, are behind most of the manufactured confusion and sticky lies around climate change.

“The organized climate countermovement spends around $800 million a year in the U.S. alone, both directly and indirectly through disinformation subsidiaries creating and spreading misleading videos and social media posts that get people mad about things as innocuous as offshore wind turbines,” says Newell.

Think tanks like the Heartland Foundation and professional PR agencies used to be the most visible spokespeople for climate disinformation, but now a small army of influencers are leading the charge. These podcasters and internet personalities have no history or involvement in the environmental space, but they recognize that climate disinformation is an effective way to expand their brand, generate clicks and revenue for their content and contribute to the outrage economy. Many of them have financial ties to corporations with a vested interest in stymying climate action.

Jordan B. Peterson, for example, a psychologist and author with a massive online following who frequently spreads climate disinformation, has ties to the Wilks brothers and the conservative media outlet The Daily Wire, which they helped found and finance.

“They understand that climate has been weaponized in the culture wars and that this topic neatly connects a lot of their overarching interests like railing against woke ideology, the excesses of liberalism and state control and surveillance,” says Jennie King, senior fellow at the Institute for Strategic Dialogue.

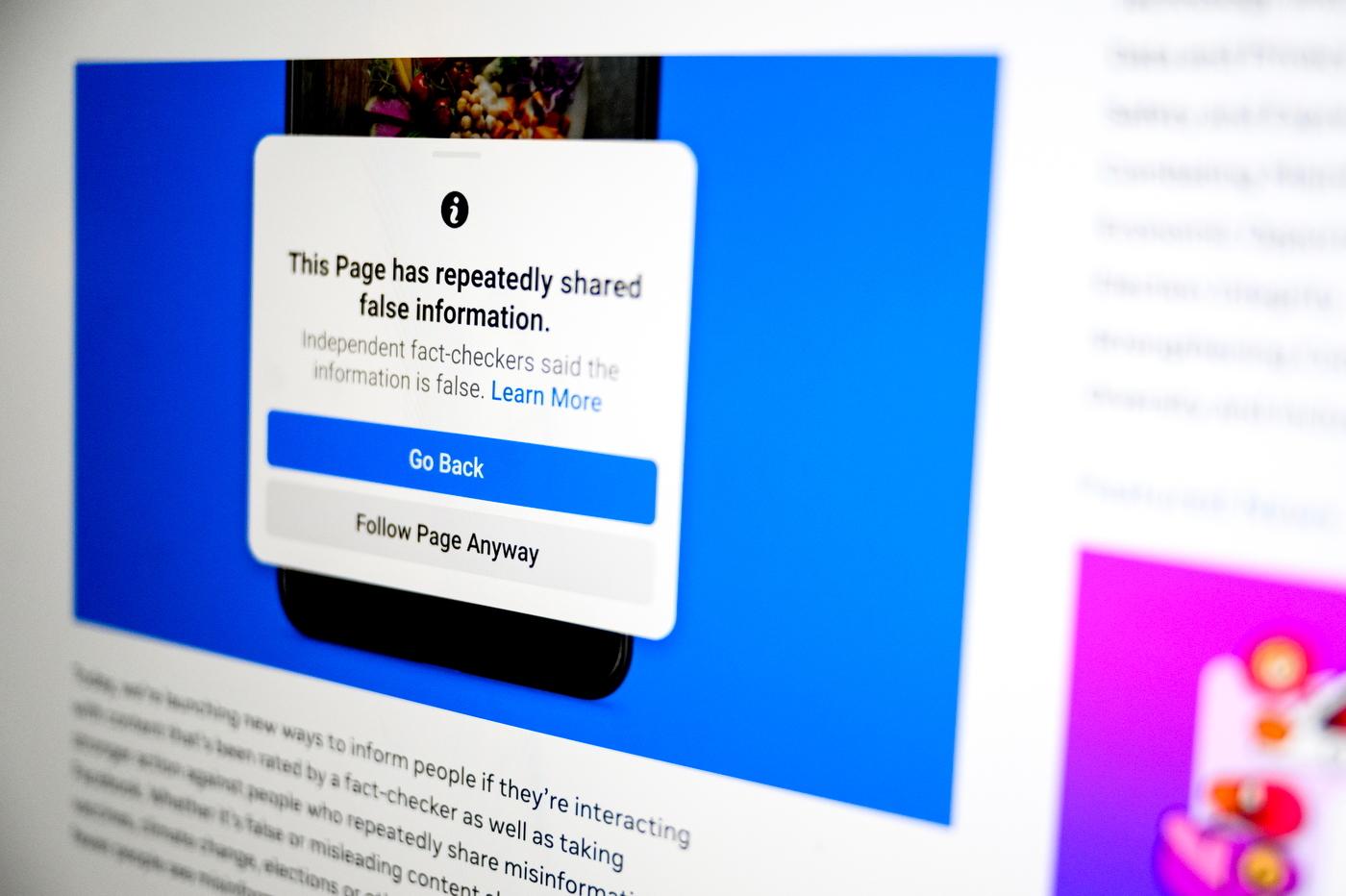

A recent study found that just ten people are responsible for 69% of Facebook climate denial. This handful of accounts is distorting the public’s image of popular opinion. And because social media platforms make more money when their users spend more time on their website and engage more with their content — and nothing drives engagement like content that makes people angry, like conspiracy theories — there is a perverse incentive for social media companies to keep the lies coming, even as more and more people rely on social media as a primary source of news and information.

Instead of cracking down on dangerous disinformation, Facebook has instead done away with its fact checking program, and X, under the pretense of defending free speech, has welcomed back with open arms people who were once banned from Twitter for spreading dangerous lies.

Environmental news that matters, straight to your inbox

Fighting back

Fighting climate disinformation is hard. After all, it’s far easier to make things up than it is to painstakingly refute baseless claims.

Leiserowitz says that no matter how many times you debunk false claims about climate, they just keep coming back again and again.

“There is no one simple tactic or solution that is going to solve this forever,” he says. “Climate disinformation is like zombies. Incredibly difficult to kill and always hungry for more brains.”

So what actually works?

Researchers at the University of Cambridge have found that educating people about common tactics used by spreaders of disinformation significantly increases people’s ability to resist it — a strategy called inoculation.

“Turning disinformation off at the source is, of course, the most efficient way to combat it,” says Elyse Martin, a climate disinformation expert at Environmental Defense Fund, a member of the Climate Action Against Disinformation coalition. According to Martin, this might take the form of social media platforms voluntarily engaging in content moderation, fact checking and adjusting their algorithms so that inflammatory disinformation doesn’t go viral and credible sources of news and information are promoted and prioritized. Or it might take the form of regulation — holding social media to the same standards as mainstream media.

The EU has taken the lead on this front with the Digital Services Act, which aims to hold social media platforms more accountable for their content and to force these companies to provide more transparency on their content moderation, algorithms and risk assessments.

The Hague has also recently made it illegal to advertise fossil fuel products and services with a high-carbon footprint, and three other cities in the Netherlands have followed suit.

In the U.S., reforming campaign finance laws to limit or eliminate corporate influence would also go a long way toward encouraging truthful, constructive discourse about climate change

Sound like a pipe dream?

Maybe. But as Newell points out, “If climate action was hopeless, no one would be spending all this money to try to stop it.”