Will Lee Zeldin leave his Long Island neighbors underwater?

Trump’s pick to lead the Environmental Protection Agency hails from an area struggling to cope with rising sea levels.

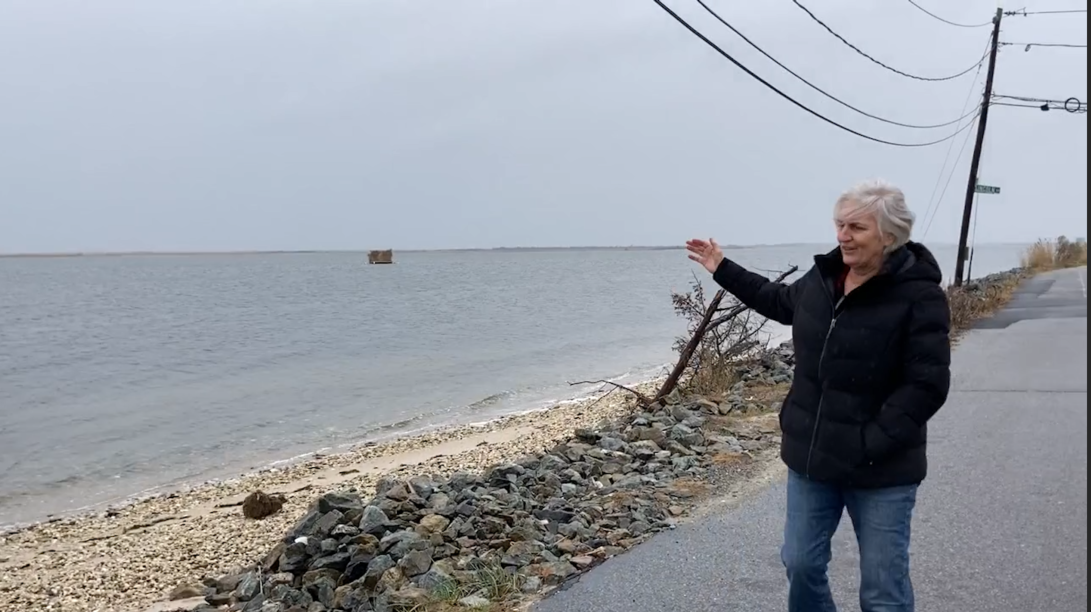

Former painting contractor Maura Spery stops her black pickup by the side of the inlet across from her home in New York’s Mastic Beach. Grey-haired with black framed glasses, she gestures out over the marsh grasses, still green in the December light.

“Look at that,” she says. The rolling tide gleams. The sun breaks through after a day of drizzle and clouds.

“Where does a painting contractor afford a view like that?” asks Spery, who has lived here for more than 20 years.

Ten miles east are Long Island’s tony Hamptons, with their rock stars and Wall Street tycoons. New York City is 70 miles west.

“I have blue herons flying overhead. I have an owl that hoots in my yard. I eat the best seafood you could ever eat,” she says of this coastal community, where she served as mayor from 2015-2017. (It’s now part of the much larger town of Brookhaven.)

This working-class hamlet isn’t exactly a seaside Eden, though.

Rising waters take a toll

Mastic Beach is facing a rising threat — flooding, once an occasional nuisance, is creating serious disruptions for people and businesses. Far from the shores of Long Island, ice sheets and glaciers are melting, and warmer ocean waters are expanding, causing sea levels to rise.

Roads near the water in Mastic Beach are now practically impassable about 40 days a year due to sea-level rise alone. No Nor’easter required. Just the full moon and high tides bringing seawater up into parking lots and residential byways like never before.

Spery and others are trying to help their hamlet stave off and prepare for the worst impacts. She leads the Mastic Beach Conservancy, dedicated to building a “blue & green” trail that will help protect marshes that buffer flooding while enabling residents to take in the shoreline’s natural beauty. Nearby, former WNBA all-star turned oyster farmer and environmental advocate Sue Wicks grows kelp that absorbs carbon dioxide — one of the main pollutants driving sea-level rise and extreme weather.

Not far offshore, there’s a wind farm under construction that will supply pollution-free electricity to nearly 600,000 Long Island homes. On Mastic Beach’s main access road, you can see workers laying electrical cable that will bring that clean power to a nearby substation.

But because reducing the pollution that is driving these changes requires national and international attention, how much the water continues to rise in Mastic Beach is mostly out of the hands of locals.

That is, except for one. Former Congressman Lee Zeldin, the Trump administration’s pick — not yet confirmed — for administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency, lives just up the road in the neighboring hamlet of Shirley.

Environmental news that matters, straight to your inbox

The agency he will likely lead is the one most responsible for helping the U.S. cut the climate and health-harming pollution that is hurting Mastic Beach, along with communities across the country and around the world. The EPA creates and enforces standards for most of the nation’s largest sources of this pollution — cars and trucks; power plants; oil and gas drilling; and methane-emitting landfills. Given that the U.S. is the world’s second-largest producer of climate pollution (and first overall, if you count historical totals) there is a lot of room for progress, as long as the EPA stays its current course.

As the new administration takes office, it’s hard not to wonder: Will Lee Zeldin help his Mastic Beach neighbors sink or swim?

Flooding is a nonpartisan issue

Every two months, State Assemblyman Joseph P. DeStefano, a Republican from nearby Medford, convenes a meeting here to discuss the problems of flooding.

Held most recently at the Mastic Beach Yacht Club, which is not as posh as the name would suggest, the meeting brought together local officials, community members and nonprofit group representatives, Spery included, in a nondescript function room spiffed up for Christmas with garlands and a tree.

The assemblyman, wearing a Santa hat and a V-necked sweater, began the session with the pledge of allegiance and a prayer.

Quickly, the group got down to business, addressing questions about Brookhaven’s efforts to elevate one of the seaside roads to keep it above water, a nearly $1 million project.

Then there is the question of Riviera Drive, once located about 40 yards inland, but now battered by the tides. The weight of parked cars on the road is undermining its integrity. Could Brookhaven put up some no parking signs to help keep the road from collapsing? Also, what about building more under- or overpasses to make sure residents aren’t held up at railroad crossings in the event of an evacuation? Further east, in the Hamptons, there are plenty of ways to get away from the coast and onto the bigger drives.

An hour and a half after it begins, the meeting ends with some kibbitzing, handshaking and happy holiday wishes; the assemblyman notes that the cost of his flood insurance has doubled in recent months.

Saltwater damages cars, fire trucks

High tide is still 90 minutes away, but out in the club parking lot, under a gray sky, the water is already starting to rise. It’s bad business for the yacht club.

“This parking lot — you can’t drive down the street unless you want to have saltwater in your car,” says Spery, who had to ditch her minivan because of the damage the saltwater did to its undercarriage.

Minvans aren’t the only vehicles at risk. “We’ve sometimes had the water 3 feet high,” says Fire Commissioner Bill Biondi, who’s been a firefighter in Mastic Beach for 53 years. “I mean, it’s a big enough issue that if the roads get flooded, we’re not taking our $1 million fire truck down there.”

It wasn't always this way. When Biondi was a kid, he says, the beaches were “100 yards, 250 yards long.” When water rose, there were still large expanses of sand between it and the bungalows that were originally built to relieve Brooklynites from the city heat.

“I would say things really started getting crappy around here right after Superstorm Sandy,” in 2012, says Biondi. Since then, the beaches Biondi played on as a kid have eroded to almost nothing. The fire company keeps a rescue vessel at the local marina between April and December. But the water’s been so high that “there was a couple of times back in November we couldn’t even get near the boat,” he says.

To answer calls when the roads flood, the fire department has had to purchase special Army surplus high-water trucks, with cabs four or five feet off the ground.

Biondi says the company has yet to have an instance where they weren’t able to help people in emergency situations. But the potential is there. As new flood-risk maps the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration published this summer show, U.S. coastal waters are only expected to rise.

What can Zeldin do?

Well-regarded studies forecast that U.S. climate pollution could fall by between 38 and 56% by 2035, if the country stays the course on its current climate laws and standards. Tailpipe pollution from cars and trucks, at present the largest sources of greenhouse gas pollution in the U.S., could drop by nearly 50%, thanks to EPA standards issued in March. Power plant pollution could fall by as much as 90%, again thanks to EPA rules. Methane leaks could drop by 80% under standards issued in December 2023.

President-elect Trump has made it clear that he intends to contest critical EPA climate and clean air standards. In news interviews following his nomination, Zeldin referred to a long list of regulations the President-elect seeks to repeal.

But many of these health-protective safeguards would need to go through a lengthy process to prove they were misguided or unnecessary.

“The challenges are going to come, but we know how to defend them, because the law and science are clear, and we’ve protected crucial safeguards for people and communities before,” says Vickie Patton, general counsel for the Environmental Defense Fund.

Of course, unbound by rule-of-law considerations, the Trump administration could simply choose not to enforce the standards already on the books. That decision would largely fall to Zeldin, whose home lies safely up the hill from Spery and her neighbors in Mastic Beach.

Zeldin would also oversee issues like drinking water contamination, a major issue for several Long Island communities facing threats like the solvent 1, 4-dioxane. In November, the EPA determined the chemical can cause cancer and other health problems.

By law, the agency must now create a program to protect Americans from 1,4-dioxane's risks. But the Trump administration reportedly plans to disrupt the EPA’s effectiveness by moving its headquarters out of Washington, meaning many of its experts, including its chemical safety specialists, would have to choose between transferring to faraway states or keeping their jobs.

Zeldin’s Senate confirmation hearings are expected to begin in Jan. 16. What he will actually do to cut the pollution that is hurting his own backyard remains unclear. When it comes to climate change, Zeldin has said he is “not sold yet on the whole argument that we have as serious a problem as other people are.”

What comes next?

Spery climbs the steep set of stairs that leads to the first floor of the home she shares with her partner. It is maybe 50 yards from the bay. After Hurricane Sandy, with taxpayer help, the pair had the house elevated 14 feet – first lifted up on jacks and then on support structures built underneath — to protect against future flooding.

From the windows, one can look out across to the soothing sea. For the moment, the water is calm. The tide has receded.

What does the future hold for the people of Mastic Beach?

That could be in Lee Zeldin’s hands.