In the Wild West of water, residents set politics aside to protect their future

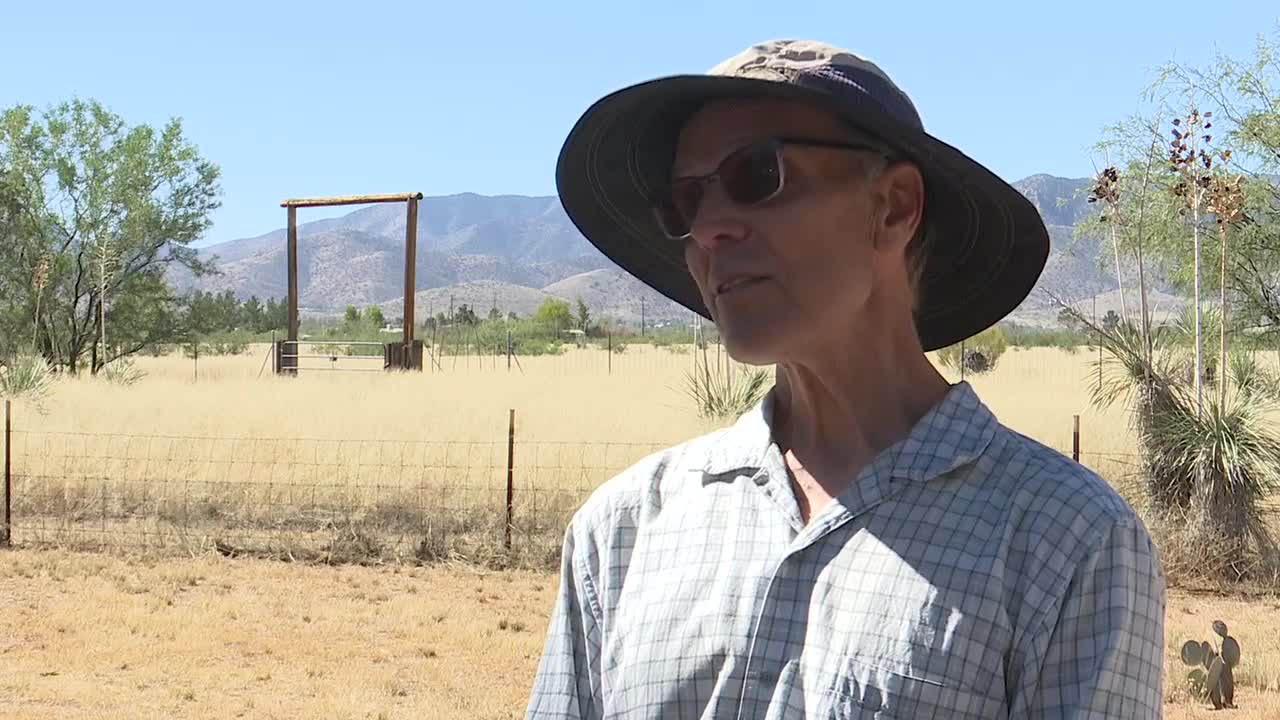

When Steve Kisiel was looking at property in the high desert east of Tucson, Arizona, he made sure to check out the water situation first. There was no city water in this rural area, so he knew he would need a good well. At 370 feet deep, the well on the property dipped securely below the water level.

“There was a reasonable supply, and it seemed stable,” says Kisiel.

So he built his dream home here, out of straw bale, in the mesquite-dotted grasslands of Cochise County, with a little garden and views of seven mountain ranges.

That was in 1998. In 2012, even though he and his wife only lived there part-time, the well ran dry. In a little over a decade, the water level had dropped more than 100 feet.

Draining Arizona

"In about 75% of Arizona, there’s no limit on how much water you can pump out of the ground,” says Chris Kuzdas, who works on water issues across the state for Environmental Defense Fund. “Whoever’s got the longest straw can come and take as much water as they want for free.”

And come they have. In 2014, a Saudi Arabian conglomerate began growing thousands of acres of alfalfa in Arizona to feed the kingdom’s cattle. Corporate nut growers planted pistachio and pecan trees where scrubby mesquite once grew. Private equity firms bought farmland simply to sell the water rights to newly developed Phoenix suburbs.

In 2014, Riverview, a Minnesota-based dairy operation, bought a feedlot near Kisiel's house in Cochise County, expanding it from 10,000 to more than 150,000 cows. In Minnesota, Riverview would be required to monitor and report its groundwater use. But here, the company had no such concerns. It drilled hundreds of wells, some of them more than 2,000 feet deep, to grow hay, corn and alfalfa to feed the cattle. In a few years, full of Arizona feed and water, the heifers are then shipped back to Midwestern dairies.

“You might as well stick a billboard right on I-10,” says Kisiel. “Welcome to Arizona, come take all our water.”

Mining for water

Nearly every drop of Cochise County’s water comes from ancient underground deposits, where the region’s sparse rainfall has percolated through rock and collected underground over millennia. Much of this water lies underneath a roughly 2,000 square mile depression called the Willcox Basin.

Cochise County has a long history of farming, ranching and mining. The wild west mining town of Tombstone was its original county seat. Today, ghost towns outnumber the cities. But for decades, groundwater from the Willcox Basin has managed to support towns like Willcox, population 3,000, as well as hundreds of other homes, ranches and farms spread out across the basin. It’s a place where people pursue their passions and are fiercely protective of their land and their independence.

Ed Curry, a fourth-generation farmer and a global expert in chili pepper breeding, grew up on a farm south of Willcox, near the Mexican border, and has been farming in the basin for decades. Curry has seen agriculture in the region wax and wane, along with concerns about water supply. When residents first started voicing concerns about Riverview, he wasn’t inclined to get involved.

“I thought the economics would take care of it,” he explains. “In the past, when farmers couldn’t get financing to irrigate all their acres, wells would idle and the water would come back.”

“Boy was I wrong,” he says. “I never dreamed the corporates would come in like that.”

Instead of letting pumps go idle, deep-pocketed corporations like Riverview simply paid to drill ever deeper. By 2018, all of the Willcox Basin’s groundwater above 409 feet was gone. Domestic wells are usually less than 400 feet deep.

By that time, Curry had already started converting his farm into a low-water-use operation. He started using drip irrigation and gave up alfalfa for rosemary and other crops that use a fraction of the water. But even he noticed a difference after the Riverview expansion. “When they started drilling really deep, that got my attention,” said Curry. “I had wells I was not even using, and they were going down. Fast.”

In a 2023 report on the basin's water, state scientists wrote, “there is insufficient annual supply to meet yearly demand under any projected scenarios.”

Environmental news that matters, straight to your inbox

Sinking earth

Dry wells weren’t the only sign of trouble. Outside of Willcox, Janet Randall’s home was breaking in half.

Randall first noticed the signs around 2012. Her doors weren’t closing properly. Then came cracks in her slab floors. Then the walls started cracking, bricks popping out, a gap in her kitchen wall big enough to let in the desert sun.

“I didn’t know when the roof was going to cave in,” says Randall, a former cement worker, horseshoer and ostrich farmer, who bought the house with her partner 28 years ago.

The diagnosis? With so much water being pumped out of the earth, the land was collapsing on itself. Giant fissures cracked the earth where the land had fallen, damaging roads, highways, wells and homes. State geologists determined that land in the fastest-sinking part of the valley had dropped 2.5 feet in 14 years. Randall’s house was sinking 3 inches every year.

"We had to jack up the roof to replace walls, we’re putting expanding foam in the cracks, but the upshot is, I can’t sell this house,” says Randall. “Nobody wants to buy a house that is falling apart.”

“I’m not out here looking for sympathy,” she adds. “I just don’t want people to do nothing. If we can’t get water, the town is going to die.”

A community fights back

For nearly a decade, concerned residents have been gathering information and discussing solutions, but consensus has been hard to build. Neighbors live miles apart, gathering places are few, and many residents have strong feelings about keeping the government out of their business.

In 2022, a groundwater protection measure on the ballot failed. Several bipartisan bills in the state legislature never made it out of committee. Fears of government overreach and accusations of outsider interference abounded.

Much of the local frustration over the water situation is directed at Riverview and at long-time state legislator Gail Griffin, who represents the area and chairs the House Natural Resources, Energy and Water Committee. Her committee has thus far failed to advance multiple legislative proposals to allow communities to manage their local groundwater. In an August 2023 op-ed, Griffin explained her actions: this “bad legislation,” she wrote, would allow “unaccountable bureaucrats to decide the community’s economy and tell you what you can and cannot do with your private property.”

Ed Curry fourth-generation farmerWater isn’t Republican or Democrat. When your well is dry, it’s dry.

“I am furious about that continued line of misinformation,” says Lisa Glenn, 81, a retired schoolteacher from Willcox who advocates for groundwater protection. “It's made it hard for our community to come together. Every year that we don’t get a handle on this, our aquifer drops lower and lower.”

Randall is equally incensed. “You say you want to keep the government out of your life? Well, if I came to your house and stole from you, like they’re stealing my water, and vandalized your house, like what’s happened to mine, you would want the government pretty damn quick, wouldn’t you?”

Action at last

While elected officials refused to change the status quo on groundwater, the state was still in the grips of a 40-year-long drought, fueled by climate-warming pollution. The situation was going from bad to worse.

But over the next two years, the tide of public opinion turned. It wasn’t just scattered domestic wells running dry. The town of Willcox had to deepen its wells, which serve more than half of the basin’s 8,000 residents, at taxpayer expense. The new governor, Katie Hobbs, who campaigned on water issues, was listening to rural communities across the state. When Hobbs established a bipartisan Water Policy Council, she tapped Ed Curry to join. State water officials held public hearings and shared data about water levels and land subsidence in the basin. The movement to protect groundwater was reaching critical mass.

“Water isn’t Republican or Democrat,” says Curry. “When your well is dry, it’s dry.”

In January 2025, the state water department designated the Willcox Basin as an active management area, which puts a stop to expanding irrigation. Major water users will now have to conserve, measure and report their use. Community members are working with water officials to develop a local water management plan. The governor has also invested $60 million in water protection, including groundwater monitoring and research.

"For more than forty years, rural communities who want to protect their groundwater supplies have been ignored,” says Kuzdas. “Now people have hope that they can finally have a say in how they manage their own water, and their future."

In Willcox, Kisiel hopes a new management plan will encourage low-water-use economic development and bring the community together around a common goal. “No one wants to see anyone go out of business, but we need a plan that’s going to stabilize things in a reasonable amount of time. Is it 20 years, 30 years? A lot of us won’t be around when it gets there, but we want to make sure it gets off to a good start.”

Arizona state lawmakers from both parties are now negotiating a groundwater bill that could help rural communities like Willcox.

“There’s a lot of things we can do,” says Curry. “The one thing we can’t do is nothing.”