When gas is your neighbor

Smog-forming and cancer-causing chemicals increase health risks for people living near natural gas and other polluting facilities. Community advocates are applauding Biden's pause on building new natural gas export terminals.

Lake Charles, a small city of about 80,000 people in southwest Louisiana, has seen its share of greatness. It’s the hometown of Judge Norma Holloway Johnson, the first Black woman appointed to the federal bench, in 1980; lauded playwright Tony Kushner, who set his musical Caroline, or Change in Lake Charles; and numerous professional athletes, including NBA Hall of Famer Joe Dumars.

But Lake Charles has also seen more than its share of disaster — the city was leveled by Hurricane Laura in 2020, and then struck again hardly six weeks later by Hurricane Delta.

Calcasieu Parish, for which Lake Charles is the seat, is one of the most climate-vulnerable places in the nation, according to a mapping analysis by Environmental Defense Fund and Texas A&M. The potential for flooding, high number of polluting facilities, lack of government services and other factors all contribute to its high ranking.

According to Louisiana’s Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority, within the coming decades, floods from a 100-year storm event would submerge areas around Lake Charles and the Calcasieu River in 15 feet of water. Nearly all of neighboring Cameron Parish would see similar increases in flooding.

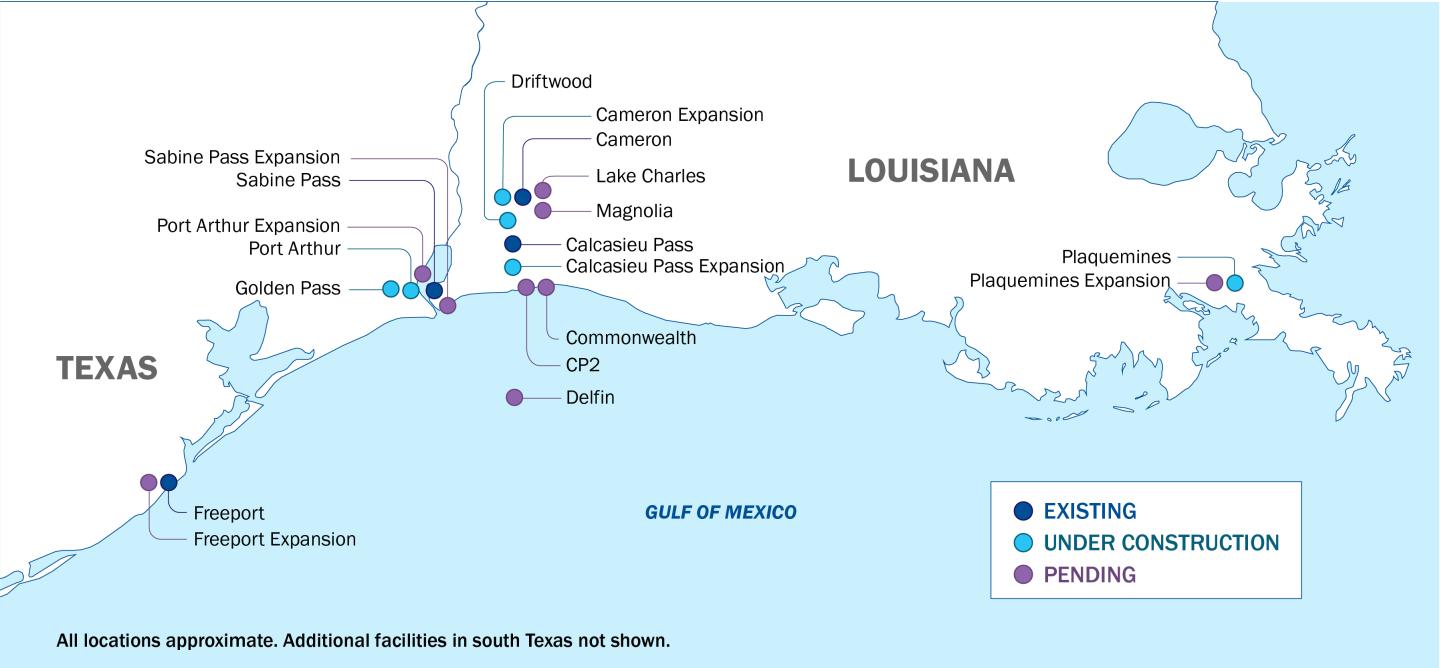

Despite that vulnerability, a new natural gas export terminal complex is under construction just south of Lake Charles. Five more are planned or seeking approval in both Calcasieu and Cameron parishes, two of them in Lake Charles itself. And three more are underway or planned just across the border in Texas.

The natural gas export boom, as the industry seeks to ship abundant U.S. shale gas overseas, is taking a toll on communities not only near drilling sites but near export facilities as well.

U.S. Gulf Coast Liquid Natural Gas export terminals

A cluster of liquified natural gas facilities is developing on the border of Texas and Louisiana. (Source: FERC, April 2024)

Biden’s LNG pause

Natural gas facilities release methane, a powerful climate pollutant, and also emit smog-forming and cancer-causing chemicals.

In early 2024, President Biden announced a temporary pause on approvals for new natural gas export facilities, most of them destined for southwest Louisiana and southeast Texas. Scores of community groups in the region applauded the move as a good first step.

“For those of us who live in the shadow of gas export terminals, and see their toxic flares night and day, [the] decision to pause gas export terminals and overhaul the review process is very welcome news,” said John Allaire, a retired oil and gas worker from Cameron Parish, in a press statement.

The U.S. already exports nearly half its natural gas supply, the bulk of it from five terminals on the Gulf Coast of Texas and Louisiana. Seven more export terminals are already under construction in the same region, and will serve to double U.S. export capacity by 2027, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration.

The U.S. already leads the world in natural gas exports, and Biden’s temporary pause, announced in late January, does not affect the projects already underway. What it will do is delay decisions on some 17 additional proposed facilities, 15 of which would be in Louisiana and Texas.

The pause is intended to give more consideration to the climate and health impacts of these additional facilities. If approved, they could lock in decades of additional climate and air pollution.

Living with “natural” gas

One of the proposed projects would expand Venture Global’s 1,000-plus acre Calcasieu Pass natural gas export terminal; the company has also proposed building a new terminal, CP2, right next door. According to analysis by the watchdog group Louisiana Bucket Brigade, Calcasieu Pass racked up more than 2,000 permit violations in 2022, its first year of operation, for incidents such as intentional releases of natural gas — which contains climate-polluting methane, asthma-inducing and cancer-causing chemicals — directly into the atmosphere.

Local residents have also documented scores of flaring incidents that have gone unreported. But instead of requiring the facility to comply with the law, Louisiana authorities simply raised the limits on its pollution permits. State authorities in Texas have done the same for LNG facilities just across the border.

“When you look at this industry, there are health risks and safety risks that are very real concerns for communities on the ground,” says Dionne Delli-Gatti, who leads EDF’s community engagement work. “These facilities are concentrated in the same areas where petrochemical facilities are, and both of them are expanding.”

According to research from EDF, Boston University and others, air pollution from oil and gas production alone contributed to 7,500 deaths, 410,000 asthma attacks, and 2,200 new cases of childhood asthma in 2016. Living near petrochemical facilities has been linked to increased risk of several types of cancer, adverse birth outcomes, asthma and kidney disease.

Communities across the Gulf Coast have been battling pollution from oil and gas and chemical facilities for decades. These facilities are often clustered in low-income communities and communities of color, due in part to a long history of discriminatory policies. Many of them also have a history of violating environmental laws. An EDF analysis of more than 200 U.S.-based petrochemical facilities demonstrated that more than 80% were noncompliant with existing laws in the past three years.

Some residents describe their communities as “sacrifice zones,” where their health is put at risk in order to supply others with products like fuel and plastic.

EDF’s Chemical Exposure Action Map reveals a cluster of additional pollution sources in Calcasieu Parish. At least 10 industrial facilities, mostly petrochemical producers and refineries, collectively release millions of pounds of some of the most toxic chemicals into the air, land and water every year.

The Environmental Protection Agency is currently considering limiting the use of some of these chemicals. However, in most cases, the agency evaluates the health impacts of each chemical in isolation — not the compounded health risks faced by people exposed to multiple pollutants that cause the same harms at once.

“Communities living at the fenceline of industrial pollution are often exposed to multiple toxic chemicals and harmful pollutants — and at higher levels than other communities,” says EDF health scientist Paige Varner. “They may also be subject to other non-chemical stressors that induce the same health effects, and thus worsen the effects of the toxic chemicals.”

What’s next

Public health experts, advocacy groups and members of the public are urging the EPA to revise how it assesses chemical risk. At the same time, tools like EDF’s Climate Vulnerability Index and the Chemical Exposure Action Map provide regulators and local communities with valuable data that can help inform advocacy, decisions around permitting, and where to direct federal funding for climate, clean energy and environmental justice programs.

On the question of natural gas expansion, it’s unclear how long the pause on new facilities will last, or what the outcome of the new review process will be.

In a recent letter to the President and Secretary of Energy Jennifer Granholm, community leaders cited concerns about risks of explosions, fishing impacts, inflated job claims and other issues that the Department of Energy should address as it considers new projects.

“The pause on export facilities is only as good as the decisions that come after,” they wrote. “We live daily with the impacts from global dependence on the fossil fuel industry...This process has to be more than just updating the numbers in your existing reports. It has to be a time to expand your analysis to include the issues that deeply affect our lives.”