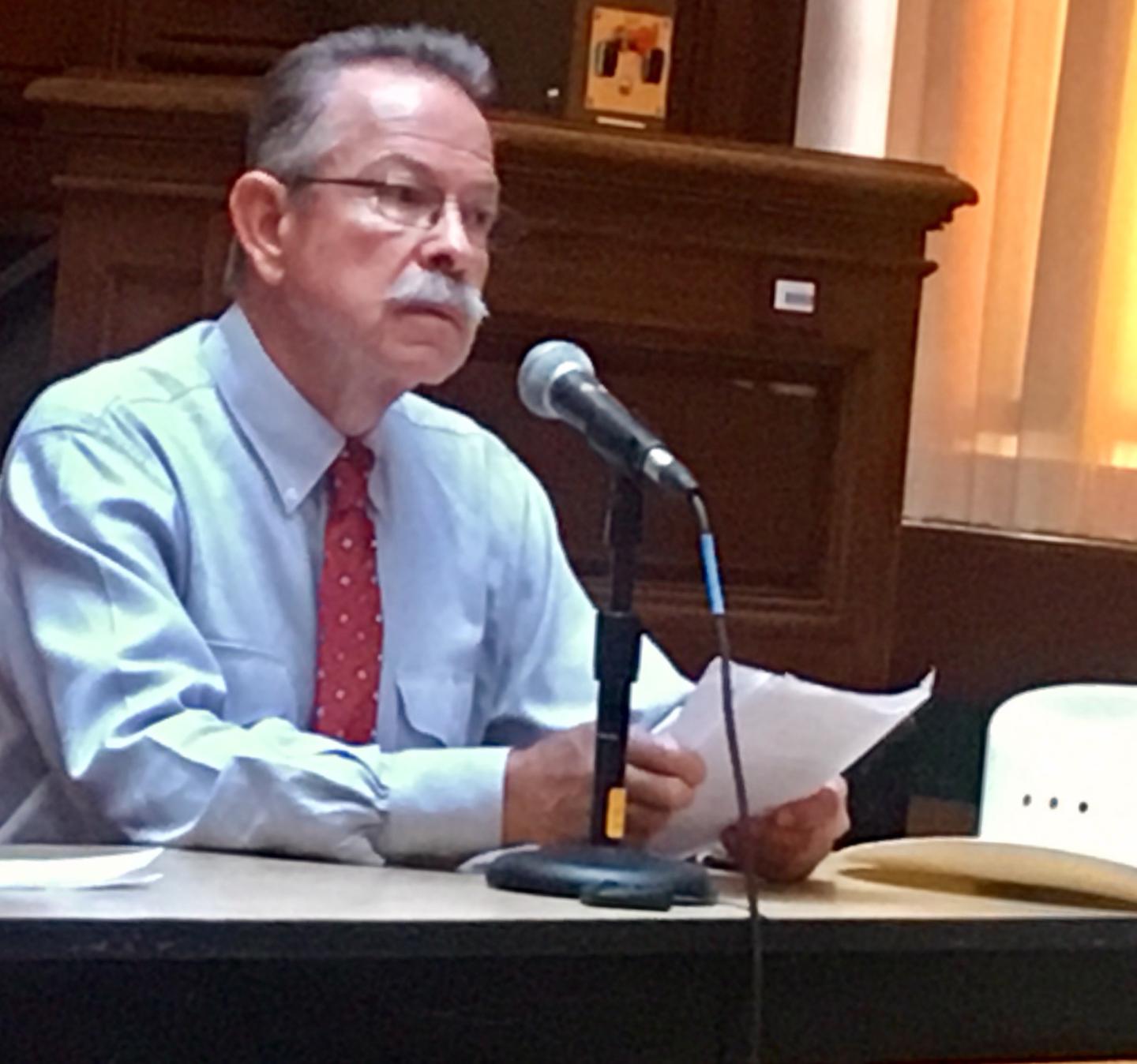

Meet the rancher exposing the dangers of natural gas to our health and planet

In 1999, Don Schreiber was eager to retire and start a new life. After decades in the insurance business, he bought 3,000 acres in the picturesque northwest corner of New Mexico, the state where he was born and raised. He and his wife, Jane Schreiber, began making plans to practice sustainable agriculture, graze cattle, ride horses and enjoy the outdoors with their grandchildren.

Then a drilling boom took off, and the Schreibers learned that their dream ranch was also rich in natural gas. The couple began receiving “intent to drill” letters notifying them of new natural gas wells that would be drilled on their property — one after another.

In 2007, they received nine from ConocoPhillips.

“Our ranch is what’s called a split estate,” Don says, explaining that while they own the land, they do not own the mineral rights beneath the surface, a common distinction in the western United States. It’s a legacy of a 1916 law that allowed the federal government to maintain mineral rights in the west as settlers claimed acres of land. The minerals under the couple's ranch still belong to the government.

Still, they thought it was “insane” that a company could just drive onto their ranch and drill. So they decided to fight back. “I cashed in a life insurance policy to get some ready cash and I began a dedicated campaign to try to save what we had,” Don says. He began meeting with regulators and political leaders in both Santa Fe and Washington DC. With so much of their time and attention spent trying to stop the wells, the couple had to scale back their ranch until they eventually had no cattle at all.

“Gas wells are not good neighbors.”

Despite their efforts, the Schreibers couldn’t stop the drilling. There are now 122 gas wells on and around their property owned by Hilcorp Energy. In 2021, the New York Times reported that Hilcorp emitted almost 50% more methane emissions from its operations than Exxon Mobil, despite pumping far less oil and gas.

Across the U.S., 18 million people live within a mile of active oil and gas wells. Each one comes with a road, trucks — and health-harming pollution. “Gas wells are not good neighbors,” Don says.

The adverse health impacts of drilling for natural gas come from the co-pollutants that are released with the methane, explains Environmental Defense Fund’s Jon Goldstein, who directs EDF’s methane regulation work. “Carcinogens like benzene can leak out,” he says. “Other co-pollutants lead to smog and poor air quality.” Poor air quality exacerbates asthma in children and is linked to both respiratory and cardiovascular diseases along with cancer.

As more wells came in, the Schreibers began limiting where their young grandchildren could go on their ranch. “We’re cautious with the grandkids because they are so much more susceptible to pollution than we are,” Don says. Researchers from Yale found that children born within two miles of active well sites are up to three times more likely to be diagnosed with leukemia before the age of 7.

“You don’t need any training to know that what’s coming out of these wells is bad for you,” Don says. “If I’m near a well that’s leaking or purposely venting the methane and those chemicals — there’s a raw gasoline-type smell that makes your eyes water.” Oil and gas companies routinely release, or vent, gas that they're unable to capture during normal operations.

- Cutting methane doesn’t just slow warming — it improves health

- What is methane and why is it such a big deal for climate?

The Schreibers can see 10 wells from their house. While they can’t prove that pollution from the wells caused it, Don suffers from heart disease and Jane has developed cancer.

Finding a solution

Cutting human-caused methane emissions by 45% by 2040 would improve air quality enough to prevent 255,000 deaths from respiratory and cardiovascular diseases globally every year. The good news is that the oil and gas industry already has cost-effective ways to cut its methane emissions. In some cases, it’s as simple as tightening a leaky valve.

In addition to mitigating some of the immediate health hazards, cutting methane pollution is also critical to slow global warming.

EDF research shows that methane has 80 times the planet-warming power of carbon dioxide in the first 20 years after it’s released. In fact, methane is responsible for more than a quarter of the global warming we are experiencing today.

In the San Juan Basin, where the Schreibers' ranch sits, tons of planet-warming methane leaks from oil and gas operations every day. “In 2014, satellite data showed the strongest concentration of methane pollution anywhere in the U.S. centered over the San Juan basin,” Goldstein says.

A warming world brings additional health risks including an increase in heat-related illnesses, poor air quality from wildfires, as well as the risks that come with extreme flooding, stronger hurricanes and prolonged droughts.

“Under the current governor, New Mexico has some of the strongest oil and gas methane rules in the country,” says Goldstein. “That’s because of people like Don as well as other advocates and tribal groups there.”

But Goldstein points out that air pollution doesn’t stop at state lines, and more federal regulation is critical. He’s encouraged by the U.S. EPA’s recent announcement of its strongest-ever methane rules for the oil and gas industry. The rules, which will be implemented over the next several years, include fining companies for excessive methane pollution.

Reducing methane pollution also received global attention in December at COP28, the UN’s annual climate talks. By the time the summit ended, more than 50 major oil and gas companies signed a pledge to slash their methane pollution to nearly zero by 2030. To ensure the companies follow through, EDF and allies, including the International Energy Agency and the U.N. Environment Programme, launched a partnership to track and report these companies' progress using satellites, including from EDF-subsidiary, MethaneSAT.

In New Mexico, Don runs tours of the pollution plaguing his ranch. He routinely takes industry leaders and regulators out to the wells on his property so they can “see” the plumes of methane pollution leaking through a special infrared camera.

“We’re bringing that ‘grease under your fingernails’ life experience to these decision-makers,” he says. “I feel an obligation to raise awareness about what’s happening here because it affects people around the world.”