From sea to table

Traditional aquaculture paired with modern science could make farmed seafood more sustainable.

According to Hawaiian folklore, Kū‘ula-kai was a divinely-inspired fisherman who built the first fishpond, or loko iʻa, on the island of Maui.

Kū‘ula-kai discovered that if he built an enclosure at the point where freshwater flows into the ocean, he could attract and capture juvenile fish that eat the small creatures that thrive in brackish water.

Hawaiian fishponds are one of the world’s many traditional forms of aquaculture — the cultivation of aquatic animals or plants for food.

Australian Aboriginal communities built channels to rear eels as early as 8,000 years ago. And in Japan, Tokyo Bay seaweed farmers planted bamboo branches in shallow water to attract seaweed spores as early as 1670.

In Hawaii, fishpond use declined after the arrival of westerners, due to development and cultural changes. But today, a movement to restore fishponds is reviving the spirit of Kū‘ula-kai across the chain of tropical islands.

Many of these new farmers are combining traditional culture with modern science to farm fish in a way that is both productive and environmentally sound.

“Our vision is abundant and healthy ecological systems that contribute to community well-being,” says marine scientist Brenda Asuncion of Kuaʻāina Ulu ʻAuamo (KUA), a nonprofit which helps Hawaiians improve their quality of life through caring for their natural and cultural heritage.

Traditions revived

Communities in what is today the United States have employed traditional aquaculture to produce seafood for centuries.

Yet the U.S. ranks only 18th in the world for aquaculture production.

The country imports up to 90% of the seafood it consumes and much of it comes from places where commercial aquaculture is executed in a way that threatens marine ecosystems, endangered species and traditional fishing communities.

Now advocates are seeking to change all that.

"While aquaculture is not without risks, if done right, it can be a win for both people and ecosystems," says Environmental Defense Fund’s director of seafood and aquaculture policy, Ruth Driscoll-Lovejoy. EDF is working with communities and legislators to develop a safe, sustainable industry.

If successful the benefits could be huge.

As wild fish stocks continue to decline, aquaculture can help meet the growing demand for seafood. It can reduce wasteful bycatch — the fish and marine mammals that get caught in industrial fishing nets only to suffocate and be thrown back in the sea.

And it can have human and ecological benefits too. Aquaculture creates jobs and provides abundant, locally-sourced food while farmed seaweed and bivalves such as oysters, clams and mussels can filter water and sequester nitrogen and carbon.

- Fishing for a future: Local fishers around the world battle to feed a growing population

- Video: The forgotten fish of Chile

The key, says Driscoll-Lovejoy, is the right regulatory framework — and the right voices at the table.

There are currently no comprehensive laws to guide the growth of a substantial offshore aquaculture industry in the United States. This has stymied aquaculture development and held back research into the impacts of farming in deeper waters and best practices to protect ecosystems.

The right legislation

Recently, the path became a little less murky, with the introduction of a bipartisan measure called the Science-based Equitable Aquaculture Food Act, or SEAfood Act.

The legislation would lay the groundwork for an equitable and inclusive seafood economy while prioritizing data and science.

Under the SEAfood Act, on-the-water research projects would help determine how to build and regulate an environmentally safe and effective offshore industry.

The act would also establish a grant program for minority-serving institutions to develop leaders and the necessary workforce for a growing aquaculture industry.

As the act moves through the legislative process, Driscoll-Lovejoy and colleagues are working with local communities — including those with traditional and Indigenous knowledge — to ensure their voices are heard. For example, they are advocating for Congress to incorporate local knowledge into rules that will govern future offshore aquaculture operations.

“A durable and inclusive offshore aquaculture industry must be informed by local communities as well as academic science,” says Driscoll-Lovejoy.

For example, entities such as Washington state’s Jamestown S’Klallam Tribe have struggled to realize their plans to expand fish farming.

In response to a state order banning commercial net pens because of a perceived danger to struggling salmon, the tribe has argued that farming native species such as Pacific steelhead can be accomplished with minimal environmental impacts.

In 2022, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration proved their case. It released research showing that marine finfish aquaculture has little to no negative impact on Puget Sound marine ecosystems and native species such as salmon and orcas.

High demand for high standards

The SEAfood Act is a long way from President Biden's desk.

But as Congress considers the bill, lawmakers will be paying attention to a 2021 survey, which showed significant public support for sustainably grown, local seafood. Seven in 10 respondents would eat more seafood caught or raised in the U.S. if fish came from sustainable sources, and if there were higher safety and environmental standards on how farmed fish are produced.

To grow enthusiasm for domestic seafood farming, EDF co-founded the Coalition for Sustainable Aquaculture, which includes award-winning chefs, environmental nonprofits, industry leaders and others who support science-based and equitable aquaculture in offshore U.S. waters.

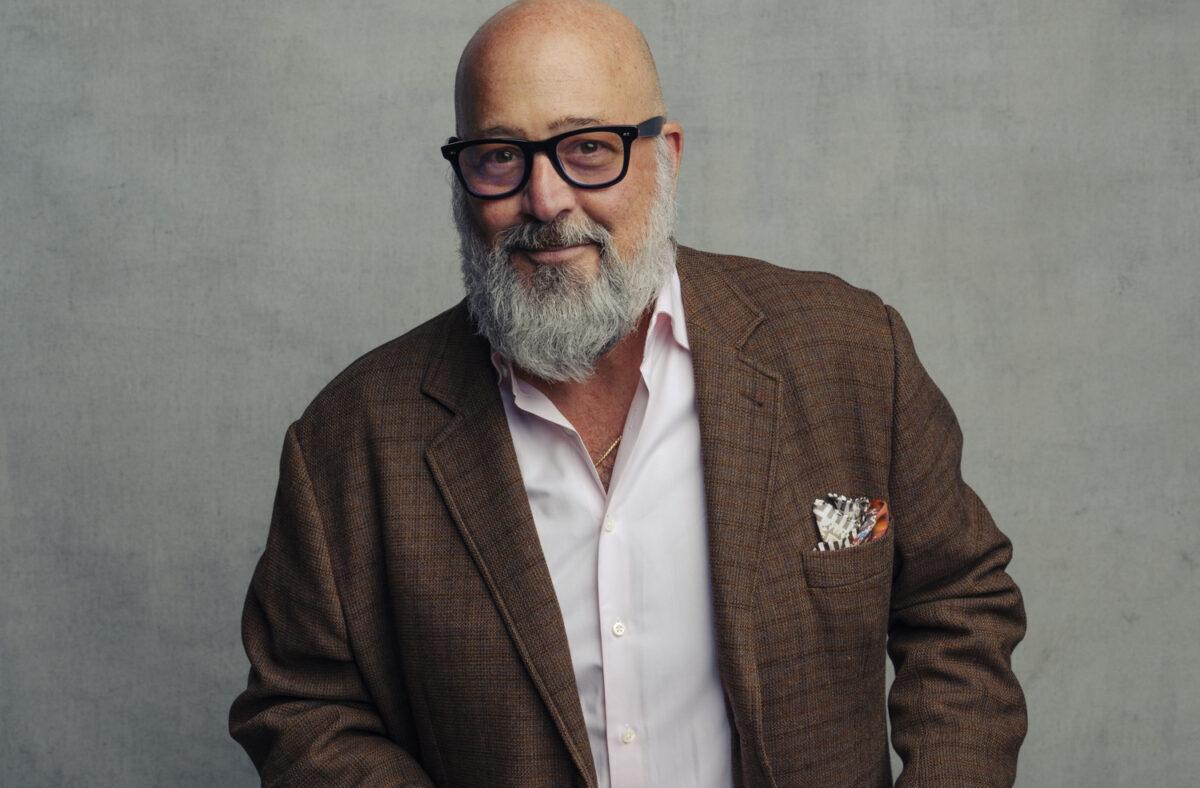

“Wild-caught fish alone won’t meet the growing demand,” says Andrew Zimmern, a four-time James Beard Award-winning chef and member of the coalition. “Growing more sustainable seafood here at home can help. But there are risks, so we have to get it right.”

For people and the planet

In Hawaii, the Alekoko fishpond was built to feed royalty more than a thousand years ago, and is still standing today.

For advocates like Brenda Asuncion, a revival of these ancient practices offers a potential to provide livelihoods to coming generations, while preserving our common resources in coastal and offshore waters.

“A lot of conservation is about protecting places from humans,” says Asuncion. “But we learned from our ancestors that in many cases it is the work of humans that helps places to thrive.”