This scientist wants climate action, and is developing the satellite to make it happen

For decades, satellites have been beaming down evidence of Earth’s changing climate — increasing temperatures, rising seas, shrinking ice caps — but with little impact. “The data wasn’t being used in the way we hoped,” says Dan McCleese, a 40-year veteran of space observation from the legendary Jet Propulsion Laboratory, and an architect of NASA’s Mars Exploration Program.

McCleese is helping change that equation with MethaneSAT, a satellite built for a single, critical purpose — to fight climate change.

He leads one of the international teams of scientists helping guide the development of MethaneSAT, scheduled to launch in 2024.

“I wanted to do something relevant to the here and now,” says McCleese. “This mission is one of those rare opportunities to make a difference.”

Reducing methane produces fast climate results

Methane is a greenhouse gas with more than 80 times the warming power of carbon dioxide in the first 20 years after its release. Because it doesn’t last long in the atmosphere, like carbon dioxide does, reducing methane emissions can have a near-immediate impact on the climate.

“Cutting carbon-dioxide emissions is important for long-term climate health, but reducing methane pollution now will result in lower global temperatures than we’d otherwise see in the next decade,” says Fred Krupp, president of Environmental Defense Fund, the nonprofit that first introduced the concept behind MethaneSAT.

MethaneSAT is built to measure methane pollution across most of the planet, with unprecedented precision and speed, and track how methane emissions change over time.

Most methane pollution comes from agriculture, including livestock, and fossil fuels, especially oil and gas. Methane is the main ingredient of natural gas, and it leaks from millions of sites around the world.

A suite of new regulations and pledges are expected to result in major methane reductions in the oil and gas industry.

In 2023, the United States issued sweeping new rules to reduce oil and gas methane pollution. The EU, one of the world’s largest natural gas importers, agreed on new rules that will slash methane pollution from the EU fossil fuel industry and possibly extend those requirements to imported fuels.

China also introduced its first national methane action plan last year. And some 50 major oil and gas companies, responsible for 40% of the world’s oil production, signed a global compact to reduce their methane emissions to near zero by 2030.

- Methane takes center stage at COP28 climate talks

- Sweeping new U.S. rules to cut global-warming methane pollution

EDF, the International Energy Agency and the U.N. Environment Programme have formed an independent alliance to use satellite and other data to track companies’ methane performance. MethaneSAT, with its unique ability to see both large emission events as well as millions of small sources, and by making its data available rapidly at no cost, will play a critical role in accountability.

“If companies fail to meet their commitments, we’ll all know it,” says Krupp.

At the cutting edge of data analysis and sensor technology

The MethaneSAT science team — which includes leading scientists from EDF, NASA, JPL, Harvard University and the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory— pushed the envelope of data analysis and sensor technology in order to make the mission succeed.

“This is an audacious effort,” says McCleese. “Credibility is key. I brought in some of the world’s very best atmospheric scientists to advise us on this. Each of them approached it with a healthy skepticism, which is what we wanted. And everyone is enthusiastic about participating because they want to see this work acted upon. They ask me, ‘Dan, is this going to happen?’ And I say yes.”

Advanced sensors on board the satellite will pick up the sun’s reflected infrared rays as they pass through the atmosphere and parse them, like a prism, to reveal methane’s unique fingerprint. That raw data will be beamed back to Earth, and a series of complex algorithms will sort through the noise — factors such as clouds, tiny particles of air pollution and the reflectivity of the ground cover all need to be accounted for — to calculate as little as a 3 parts per billion increase in methane emissions at ground level.

No other satellite is designed to locate and measure methane emissions with such precision and speed across so much of the planet.

Building on past experience

The project is ambitious, and not without risk, as McCleese knows full well.

“Making observations from space is hard,” he says. “When we started doing low-cost planetary missions about twenty years ago, we had several failures. A spacecraft burned up because the English and metric units were confused and it got too close to Mars. I could hear people shouting out the numbers, 300 kilometers, 200 kilometers, 70 kilometers … we’re done. The details can bite you.”

Those are the kind of lessons that stick.

“Experience has taught us how to work smarter," McCleese says, "focusing attention on critical details, like are the members of the team talking to each other, sharing their ideas and even their smallest doubts about the hardware? Or, if you’re adapting hardware originally designed for another instrument or spacecraft, have you done the testing to guarantee that it will work here?”

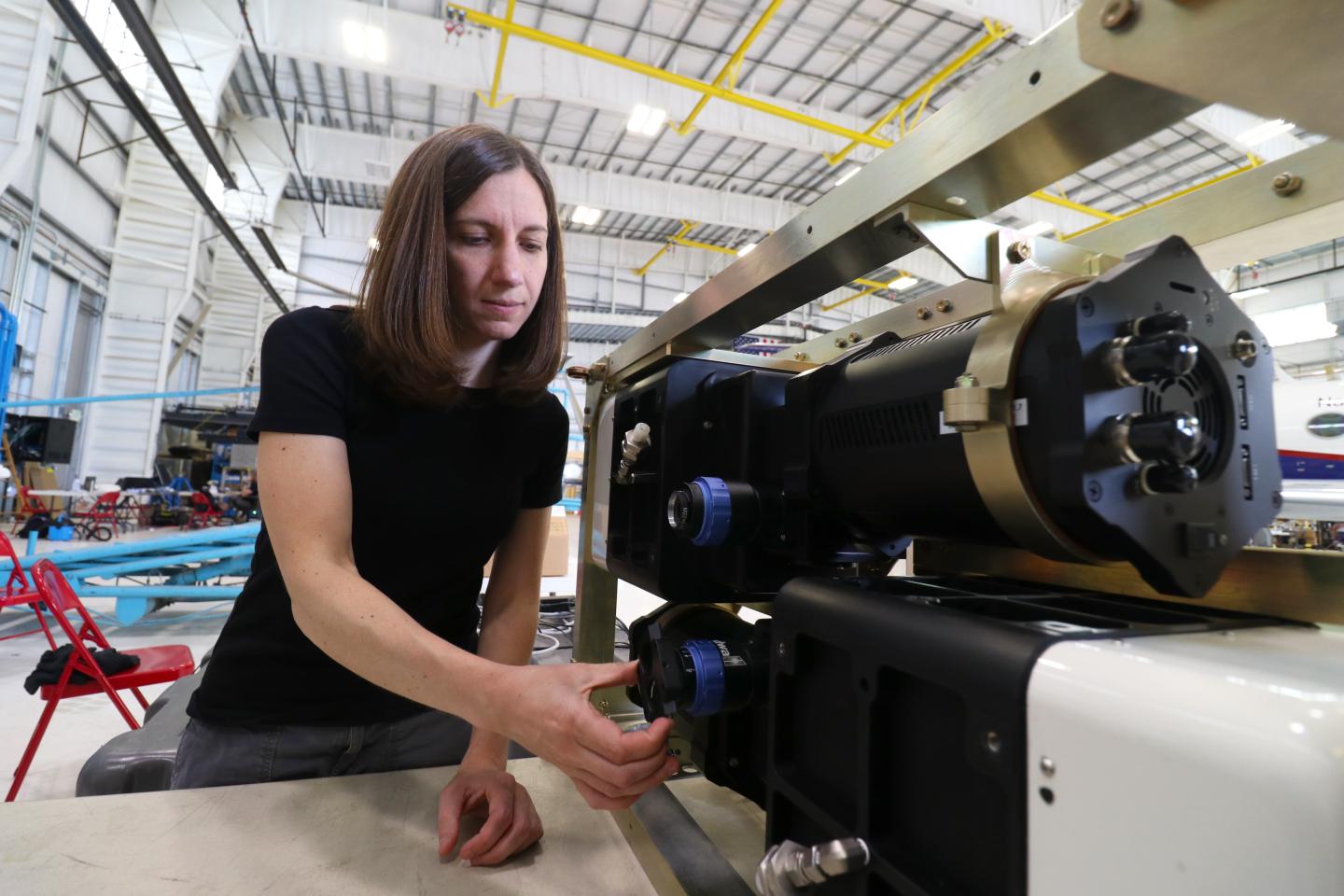

MethaneSAT construction is now complete. Its sensor technology and data analytics platform has been successfully tested on MethaneAIR, a customized Lear jet that recently flew over major U.S. oil and gas producing regions, measuring methane pollution from hundreds of thousands of small sources that have been invisible until now.

Barring unforeseen complications — which, when it comes to space, are an ever-present possibility — the satellite is scheduled to launch in early 2024.

“It’s a very exciting time for the MethaneSAT mission,” says McCleese. “What I’m really looking forward to is ‘first light’ — the moment when MethaneSAT first views Earth.”

This could be the view that makes all the difference.