The female climate scientist you've never heard of (but should have)

Eunice Newton Foote demonstrated the greenhouse gas effect three years before the male scientist credited with the discovery.

In 1856, Eunice Newton Foote conducted a relatively simple experiment at her home in Seneca Falls, New York.

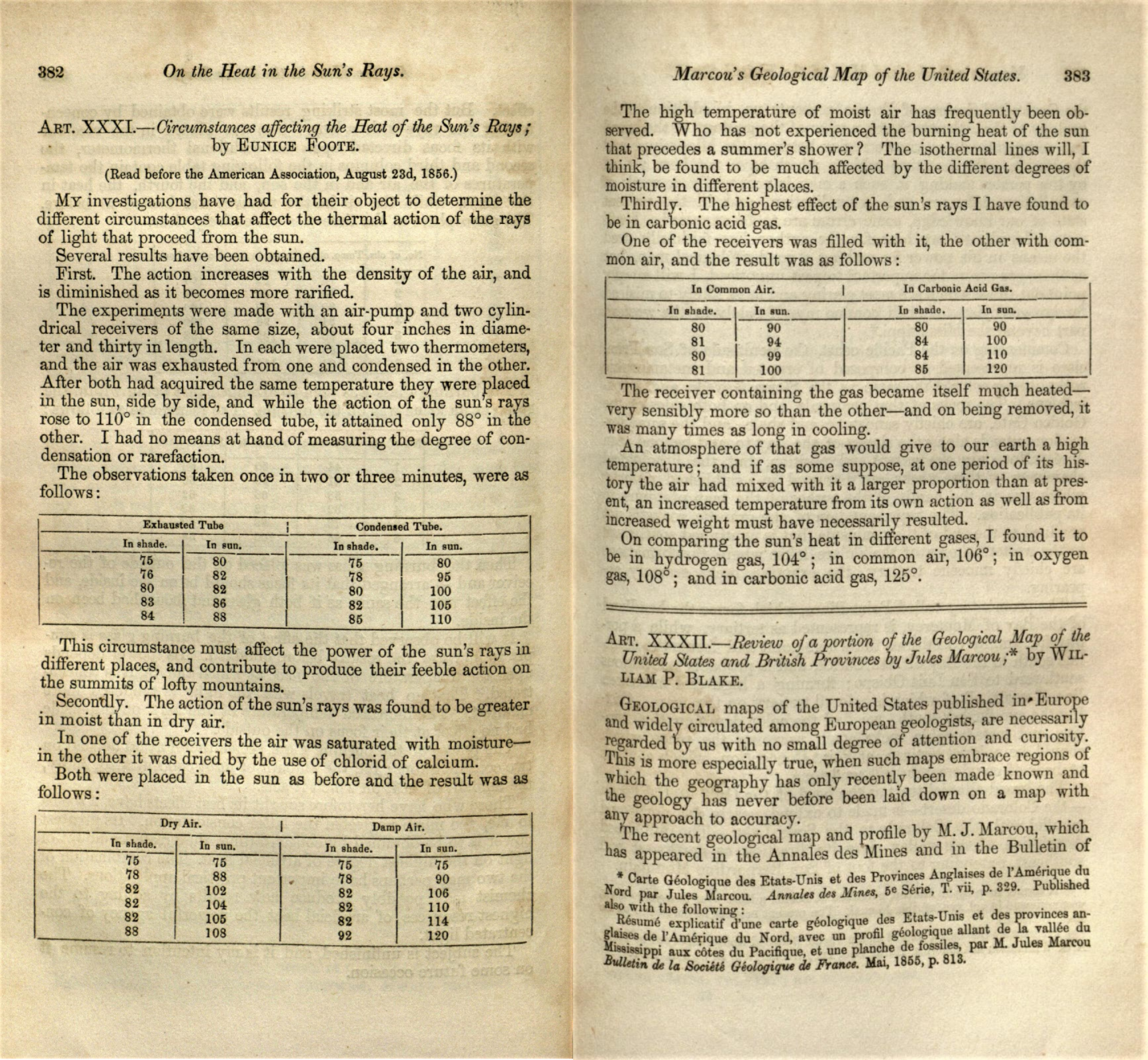

She took a sealed glass cylinder, pumped in carbon dioxide, and placed it in the sun. Then she filled another cylinder with ordinary air and placed it in sunlight as well. Each one contained a thermometer so she could monitor the temperature inside.

She found that the cylinder filled with carbon dioxide trapped more heat. Foote wrote a paper describing her findings. In it, she came to a surprising conclusion about carbon dioxide, writing: “An atmosphere of that gas would give to our earth a high temperature.”

Her experiment, conducted more than 150 years ago, predicted the climate change we are experiencing today. As humans add more and more carbon dioxide to the atmosphere by burning fossil fuels, the global temperature is going up.

She was the first person to demonstrate what we now know as the greenhouse gas effect.

And then — she was forgotten. Three years later, well-known Irish physicist, John Tyndall, conducted a more complex experiment and was credited with discovering the greenhouse gas effect.

Setting the record straight

Foote’s work didn’t come back into the narrative until amateur historian Ray Sorenson found her research more than 100 years later.

In early 2011, Sorenson, an avid collector of 19th century texts, was looking through the Annual of Scientific Discovery from 1856 when he came across Foote’s experiment. That year, she had brought her findings to the American Association for the Advancement of Science, and they were read aloud (by a man) at the group’s annual meeting in Albany.

Sorenson holds a master's degree in geology. He’s also keenly interested in the history of oil and gas exploration as well as the industry’s effect on the climate. Until that point, he thought that John Tyndall had discovered the greenhouse gas effect. But it occurred to him that Tyndall didn’t make his discovery until 1859 — after Foote’s experiment. (Whether Tyndall knew of Foote’s earlier experiment is still a subject of debate.)

“I realized that Eunice Foote deserved credit for being an innovator on the topic of carbon dioxide and its potential impact on the climate,” Sorenson says.

He posted a paper titled “Eunice Foote’s Pioneering Research on CO2 and Climate Warming” on the American Association of Petroleum Geologists website and hoped that a reporter or researcher would follow up on Foote’s story.

It worked. “That post got more attention than everything else that I’ve written combined,” Sorenson says.

Honoring a trailblazer

Today, Foote is the subject of articles, a play — even a Google doodle. The New York Times retroactively wrote her obituary in 2020.

Physicist and writer John Perlin became so intrigued with Foote’s work that he spent six years researching her life for a book that he hopes to publish this year.

“In the 1800s, most men believed that women couldn’t do science,” Perlin says. “She went totally against the grain. … She was the only woman scientist to be published in peer-reviewed journals until Marie Curie.”

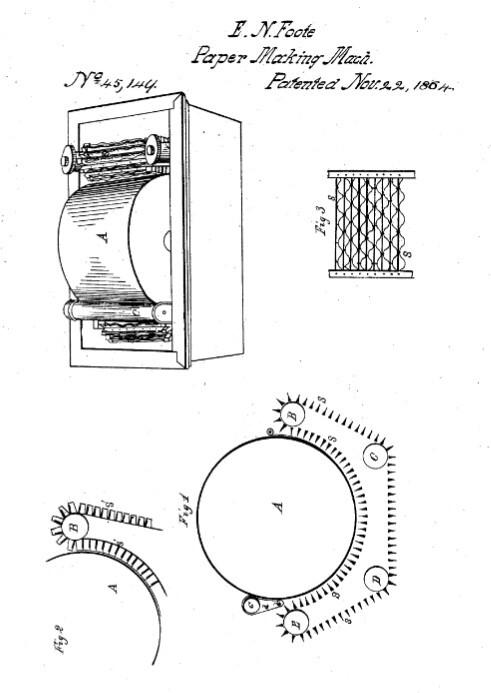

In addition to her scientific skills, Foote was active in the women’s suffrage movement alongside Elizabeth Cady Stanton. She spoke out against slavery and raised two accomplished daughters — one married Senator John Henderson, co-author of the 13th amendment, which abolished slavery. She was also an inventor. Foote and her husband, Elisha, were granted several patents. Their most successful invention was an early version of the thermostat.

Fiona Lo, a climate scientist at Environmental Defense Fund, calls Foote’s contributions “remarkable” especially given the era in which she lived.

Lo adds that, in her experience, it can still be difficult to speak up as a female climate scientist, given that the field is dominated by men. According to a 2021 report by Reuters, of the top 1,000 most influential climate scientists, just 12% are women.

“Eunice Foote must have been so strong and so smart,” Lo says. “I’m glad to see her get the credit she deserved.”

For the next generation of climate scientists, Lo has this advice: “Speak up when decisions are being made to select people as speakers or for awards, and remind them to include women.”