A nation on the move

Millions in the U.S. are leaving their homes due to extreme weather. Is any place safe?

Cindy Adair, a real estate agent in Vermont, is busier than she’s ever been. Her clients aren’t just looking for a change of scenery; they’re seeking refuge.

“Lately, I’m getting a whole lot of worried people,” Adair says. “New Orleans and Florida people coming up here to escape hurricanes. A couple from Austin who thought they might not survive if their air conditioning broke. Another family from Cape Cod who were thinking that their home will probably be washed away in 15 years — or that they wouldn’t be able to sell it because beachfront property values are diving so fast.”

Across the U.S. and around the world, more people are leaving their homes as a warming climate drives more frequent floods, storms, wildfires and droughts. Disasters forced more than 26 million people in 148 nations away from their homes in 2023 and could displace 1.2 billion by 2050.

In the U.S. and elsewhere, the vast majority of climate migrants move within their own country. But even this domestic migration is reshaping American communities.

About 2.5 million people had to leave their homes in the United States because of weather-related disasters in 2023, according to the latest census data. And for some of those who can move by choice, climate change is playing a growing role in their decisions, with buyers prioritizing climate resilience as much as schools, ocean views and urban conveniences.

Before moving his family to Waterford, Vermont last year, Dustin Kelly had lived in West Texas most of his life.

“That was the place I grew up, the place where I once felt most secure,” says Kelly. “But it was getting to the point that our A/C couldn’t keep up. We were getting close to 100 days a year of 100-degree-plus temperatures, and it doesn’t cool down at night anymore.

“The aquifers below us were running dry, so we started looking for a place with a secure water supply and cooler summers. It seemed risky to stay.”

Economics force tough choices

Climate risks like these will drive an estimated 5 million Americans to relocate this year, according to a recent study by financial research firm First Street, with more than 55 million expected to migrate in response to climate risks within the next three decades.

It’s not just the climate-driven weather that is forcing migration — it’s the cost of staying put. In 2024, there were 27 weather and climate disasters that resulted in at least $1 billion in damages. Because of losses like these, the cost of home insurance is skyrocketing in high-risk areas. Since 2019, average premiums have jumped 31%, with even sharper increases in disaster-prone states like Florida and California.

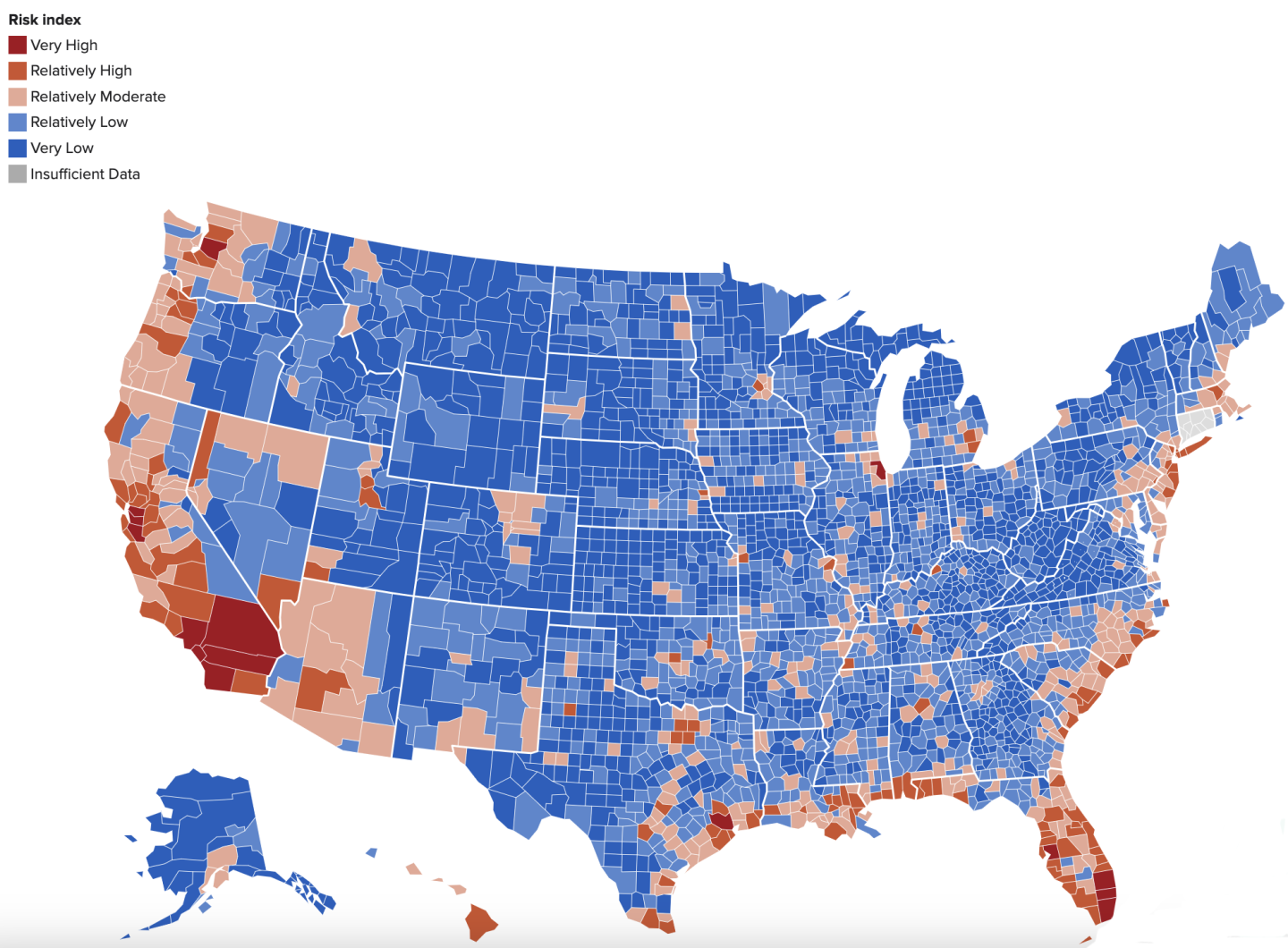

Counties at risk from climate disasters

Demographers predict that these once-booming regions will see significant population declines by midcentury. For example, by 2050, flooding events in Florida are expected to occur more than ten times as often as they do today, putting 2.4 million residents living within four feet of the high tide line at risk of displacement and forced migration.

California residents face ever-increasing risks from flooding, as well as droughts and wildfires. Paul and Allisa Zimmerman lived in Calabasas, a Los Angeles suburb, for 27 years, raising two children. “Over the past few years, the fires just kept getting closer,” Paul Zimmerman recalls. “We had to evacuate three times. We had a go-bag and we’d perfected a system where we could get away in a few minutes.”

During 2018’s Woolsey Fire, winds sent flaming tumbleweeds into the neighborhood, but firefighters managed to stop the blaze at the edge of their next-door neighbor’s yard.

“After our neighbor told us that he was having trouble getting insurance for his house,” says Zimmerman, “we started thinking that we’d better get out of there before they canceled our policy.”

For decades, artificially low insurance premiums allowed people to live more cheaply in high-risk areas, masking the true cost of climate exposure. A mix of regulatory and consumer pressures kept insurance prices low and property values afloat, helping to prevent a mass exodus from these areas. Now, as insurers hike rates to reflect higher climate risks and higher rebuilding costs, home insurance premiums are soaring nationwide — particularly in places where wildfires, hurricanes and floods are becoming more frequent.

First Street analysts found that insurance premiums underestimate climate risk for 39 million U.S. properties. In other words, 27% of all properties have premiums that are too low to cover their true climate-related risks. In some areas, insurers are abandoning entire towns, leaving homeowners with fewer options — or none at all.

Rising insurance rates are starting to influence where people search for housing, according to Environmental Defense Fund’s Carolyn Kousky, a disaster insurance expert who co-authored a recent analysis of California home loan application data. “We found that, as wildfires make homeowners insurance harder to obtain, people are rethinking where they want to live,” says Kousky. “When availability of insurance declines, buyers become less interested in high-risk homes, leading to fewer loan applications and declining home prices in those areas.”

The Zimmermans left California entirely, moving to a suburb of Detroit. In January of this year, they followed the news of the most destructive fires in Los Angeles history from their new home. They texted with former neighbors and learned they were evacuating as the flames closed in on their street.

“We’re more convinced than ever we made the right decision,” Zimmerman says. “But we’re really concerned for our friends out there.”

Environmental news that matters, straight to your inbox

In search of climate havens

For the past few years, cities like Duluth, Minnesota and Asheville, North Carolina have been drawing increasing numbers of migrants who see them as climate havens. But even these so-called safe zones are not immune to disaster.

Many considered the Pacific Northwest a climate haven until the 2021 heat dome, which caused more than 250 deaths in the U.S. and 400 in Canada. Hawaii was often thought to be a safe bet until the deadly fires on Maui in 2023. In Vermont, home to six of the 10 U.S. counties considered least vulnerable to the impacts of climate change, unprecedented flooding devastated river valleys in 2023.

When Hurricane Katrina struck New Orleans in August 2005, Alex Webber was forced to flee the rising waters in the middle of the night, with her two-year-old daughter in tow. Nine months later, they found refuge in western North Carolina. “We came here seeking higher ground,” Webber explains. Webber, her husband and daughter settled in Marshall, a small town north of Asheville, where they eventually opened a bike shop and café just a few blocks from the French Broad River.

A few miles upstream, the French Broad River winds through Asheville, where Peter Conroy, a writer for the Climate Reality Project, moved his family in 2022. His son, who has asthma, often couldn’t play outside in Colorado because of the poor air quality caused by an increasingly intense wildfire season.

On September 27, 2024, the remnants of Hurricane Helene turned both families’ dreams of finding a climate haven upside-down.

Flooding destroyed the Webbers’ bike shop and the Conroy’s house.

“But as bad as it has been for us,” says Conroy, “we know it could’ve been a lot worse. Some people lost their lives or lost loved ones.”

Cutting pollution, building resilience

“Climate change is real,” says Webber. “And if all of us don’t get our heads out of sand, it’s only going to get worse.”

Some climate impacts are unavoidable due to the amount of pollution already in the atmosphere. They will inevitably force more people to migrate.

The key to preventing a worsening crisis? “We need to double down on global efforts to cut greenhouse gases and meet the Paris Agreement’s targets,” says EDF climate policy expert Zach Cohen. Even though President Trump has begun the process of withdrawing the U.S. from the Paris Agreement, most countries remain committed and many are making progress — though at a slower pace than needed.

In the meantime, moving out of harm’s way isn’t a solution that everyone can afford. Research suggests that those left behind — particularly in the southern U.S. — will be older, less wealthy and more vulnerable to extreme weather, making recovery even harder. This underscores the urgent need to strengthen communities' ability to withstand and recover from climate-related threats.

“By upgrading infrastructure to withstand floods and investing in decentralized power grids that prevent widespread outages, we can enable people to stay in their homes safely and sustainably,” says Cohen.

Across the U.S., states and communities are taking action to build resilience against climate disasters. The Biden-era Bipartisan Infrastructure Law is funding projects to reduce flooding risks and strengthen the power grid, while California invests in grid upgrades and energy storage technologies to prevent wildfires and ensure power during emergencies.

In Louisiana, New York and Florida, with encouragement from local communities and groups like EDF, the Army Corps of Engineers has begun to embrace natural solutions like oyster reefs and wetlands combat flooding. These nature-based defenses are effective and resilient and can be used instead of or in combination with traditional infrastructure.

Whether these and other resilience efforts will move fast enough to prevent people from having to leave their homes is uncertain. What is known, however, is that without urgent action to cut emissions and slow warming, nowhere will be entirely safe from the growing risks of climate change.

Even Conroy, who has spent much of his career communicating the risks of climate change, says he didn't realize how quickly and completely a climate disaster could turn his life upside down.

“We looked at the odds and we made what we thought were well-informed decisions,” Conroy says. “We assumed we’d found a safe place where it wouldn’t happen to us. And then it did.”

Read more about Alex Webber and other climate migrants around the world in Uprooted, a series produced by Moms Clean Air Force’s Latino engagement program, EcoMadres.