As El Niño intensifies climate-related storms, the world's food producers turn to technology to adapt

Even before the storms came, María Catalán (pictured above) was no stranger to the ups and downs of small-scale farming.

After immigrating to the U.S. from Guerrero, Mexico in the 1980s, she worked for years as a produce picker, eventually scraping together enough to lease a small organic farm — only to lose it in 2014 when her well failed during California’s worst drought in 1,200 years.

This past March, after nine years of building a new 41-acre farm in Hollister, California, the rains that Catalán had often prayed for arrived in a torrent. Floodwaters swamped the fields of organic vegetables she grew for nearby restaurants, food pantries and a community-supported agriculture (CSA) program beloved by local residents.

“I watched it come down the hill and take out the cauliflower, the peas, the cabbage and the beets,” she remembers.

As the roiling water engulfed her trailer home, she and her family fled, leaving their belongings behind. They managed to escape, but their dog, Flor, did not.

“In three hours,” says Catalán, “we lost everything.”

Longer droughts, harder rains

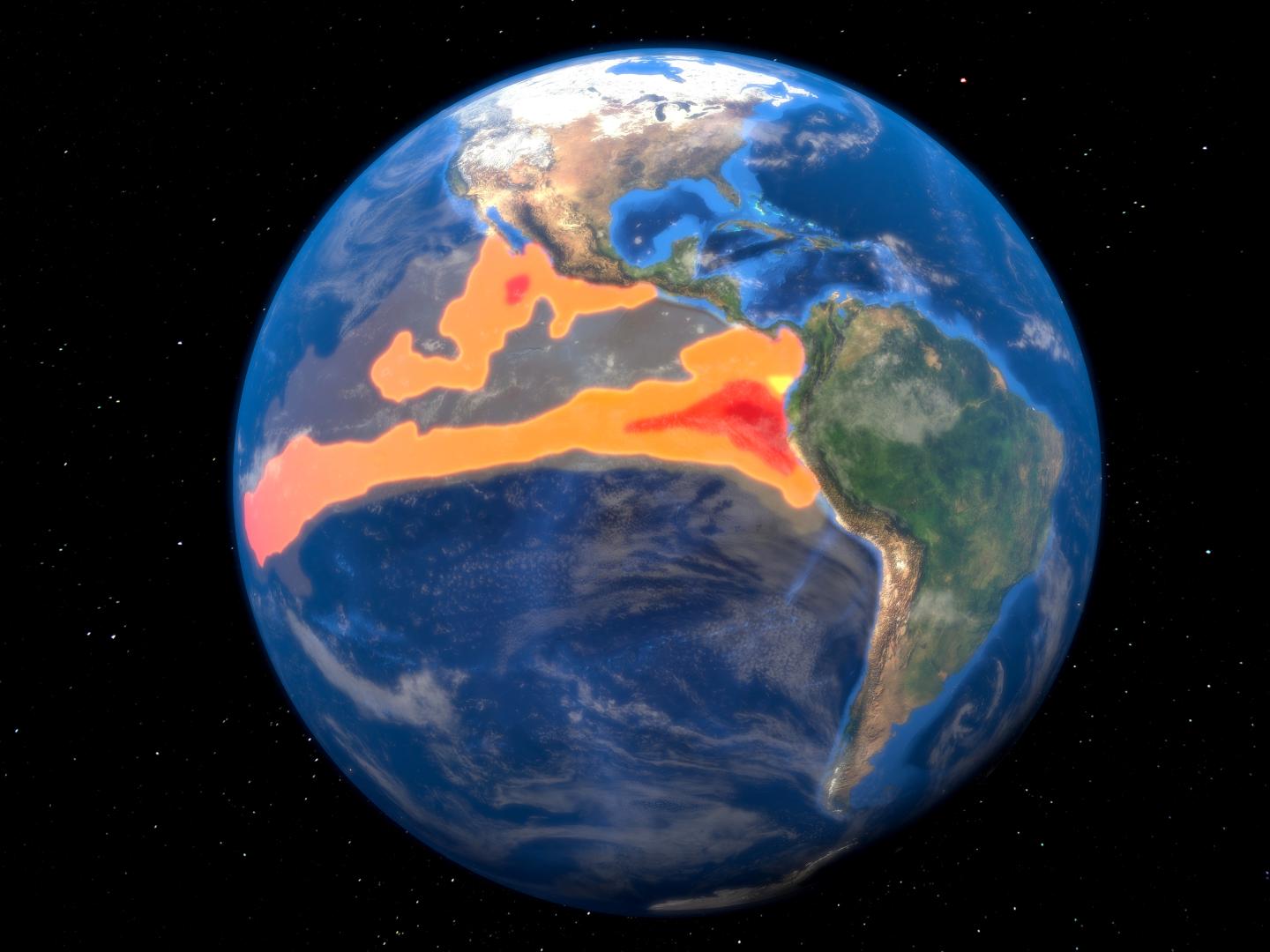

Drenching rains in northern California are a hallmark of a recurring weather phenomenon known as El Niño, when the surface waters of a large swath of the tropical Pacific Ocean warm dramatically, influencing rainfall and other weather patterns around the world.

The current El Niño, which began in early 2023 and is expected to prevail into 2024, is driving weather extremes that are amplified by climate change and devastating agriculture across much of the Americas.

“From small-scale farmers in northern California to fishers in southern Chile, the livelihoods of people who put food on everyone’s tables are being upended,” says Erica Cunningham, who leads Environmental Defense Fund’s fisheries and oceans work in Latin America. “In terms of food security, this could be disastrous for millions of people and communities that are already vulnerable to climate change.”

Record-breaking heat waves in 2023 were amplified by the arrival of El Niño, and 2024 could bring even hotter weather to places that usually see warm temperatures during El Niños.

Earlier this year, unusually warm waters helped fuel the first ever Category 5 hurricane in the Pacific to make landfall in North or South America. Hurricane Otis grew so fast that officials and residents of Acapulco, Mexico had little time to prepare before 165-mile-per-hour winds tore into the city.

In the rain shadow east of the Andes, a drought worsened by the El Niño phenomenon has shriveled the Amazon’s vegetation, fueling thousands of uncontrolled fires that have scorched more than 11 million acres. The Amazon River has dwindled to its lowest level in 121 years.

Little respite for farmers and fishers

El Niño is the warm-water phase of a recurring climate pattern called the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO). In North America, El Niño usually decreases the likelihood of a big Atlantic hurricane season while increasing hurricane activity and rainfall in the Pacific. Another phase of ENSO, known as La Niña, does the opposite — and likely contributed to extreme droughts in much of California in 2021 and 2022. Scientists at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) compare the phenomenon to a seesaw.

Dr. Jaime Letelier, head of oceanography and environment at Chile’s Institute of Fisheries Development, IFOP, says the magnitude of this cycle's seesaw is unprecedented. “Climate change is making the natural environmental variability in the Humboldt Current ecosystem — one of the world’s most productive fishing grounds — even more pronounced.”

María Catalán, 61, has been through El Niño cycles before, both in her native Mexico and in California, where this year’s storms and flooding wiped out hundreds of thousands of acres of farmland. She says conditions are steadily getting worse.

“Over a lifetime of farming, I can see the droughts getting longer and the rains coming harder,” says Catalán. “Everything is more extreme.”

In many cases, the burden of climate-intensified weather phenomena tends to fall hardest on people who are already facing multiple hardships — migrant laborers dependent on seasonal work, small-scale fishers chasing dwindling fish stocks or specialty-crop farmers like Catalán, unable to access crop insurance programs that mainly benefit large farms growing commodity crops like wheat, corn, soybeans and rice.

“The effects of a changing climate are so much worse for people who live in communities where residents are economically disadvantaged or historically marginalized, or people of color,” says Margot Brown, EDF’s senior vice president of justice and equity. “These communities face legacy pollution and health problems. They often lack adequate infrastructure and access to good health care. When you put climate change on top of existing issues it becomes a threat multiplier.”

Fallout for fisheries

The term “El Niño,” a Spanish reference to the baby Jesus, was coined more than a century ago by Peruvian fishers who noticed unusually warm water around the Christmas holiday.

In the northern Peruvian port of El Ñuro, life-long fisher Marcelino González leads a guild of 35 boat owners who are coping with near-shore ocean temperatures that reached a record high this year. González says the superheated water has reduced both the quantity and quality of the catch. Some high-value species that are often part of a day’s haul, such as tuna, have disappeared.

“No matter how much you go out looking for them, you can't find them,” Gonzalez says. “What that means is that our people have been less able to support their families and the local economy.”

On shore, the coastal El Niño brought heavy rains and flooding to northern Peru earlier this year, causing at least 85 deaths and damaging housing, roads, utilities and livelihoods. The ongoing humanitarian crisis has affected an estimated 517,000 people, according to the U.N.

“The storms wiped out our communal fishing dock, which made it impossible to get to the boats, impossible to work, impossible to bring anything home,” says Gonzalez. “For three months, this community has been in chaos.”

In the struggle for a climate-resilient food supply, technology can help

In 2022, Environmental Defense Fund teamed with the governments of Chile, Peru and Ecuador to launch a coastal ocean observing system, designed to predict changes in ocean conditions and help communities and industries prepare and adapt. The system, known as SAPO, collects data and observations each day from satellites and hundreds of instruments and monitoring stations along the coasts of these three countries. Experts use the observations to create indicators that can highlight changes in ocean and fishery conditions in the Humboldt Current.

Earlier this year, fisheries managers in Peru and Chile used SAPO indicators to issue alerts as the current El Niño emerged. Similar to NOAA alerts in the U.S., these notices allowed managers to take action (including temporarily closing Peru’s anchovy fishery to protect its long-term viability) to quickly adapt to changing ocean conditions.

SAPO is also emerging as a model for similar, land-based systems that can be used for agriculture and wildfires. Recently, the United Nations Environment Program asked for EDF’s help to develop a prediction and early warning system for wildfires in Bolivia and Brazil, whose rainforests are home to Indigenous peoples and crucial to carbon sequestration and a stable climate.

Even when the Pacific isn’t in the grip of El Niño, extreme weather is becoming the new norm. The world is expected to lose an estimated 250 million acres of crop production by 2050 due to drought and desertification, flooding and outbreaks of pests and invasive species.

In the southwestern United States, farmers make use of a platform which uses satellite data to track water use in near real-time. The Groundwater Accounting Platform, which EDF helped develop, will soon be available elsewhere in the U.S. and Latin America too.

Even as El Niño turns the lives of farmers and fishers upside down, it also inspires new ways to adapt.

“We’re learning new tricks for when mother nature throws a wet blanket on our plans,” says Nick Davis, who grows almonds and wine grapes in California’s Central Valley.

Davis built buffers and planted cover crops to capture runoff from El Niño-driven rains, allowing him to recharge the aquifer beneath his vineyards. “When drought conditions return,” says Davis, “we’ll be able to use that water.”

In Chile, small-scale fishers are beginning to employ management plans that protect more vulnerable species while allowing them to catch other species that are more resilient to El Niño conditions.

Catalán, whose neighbors have started a fundraising campaign to help her pay for some of the most urgent repairs, believes she can learn from her experience.

”I don’t know if I'll be able to keep paying the rent on my land and keep the farm,” she says. “But if I can, I hope to rebuild in ways that can cope with what’s coming next with the climate.

“My life as a farmer has been all about loss and recovery,” she adds. “I’m starting over now, and it will take years to come back. But with the help of good people and a lot of hard work, I may be able to weather this crisis.”

Hope for a warming planet

Get the latest Vital Signs stories delivered to your inbox